|

Captain Sam did a lovely video over the wreck of the sloop First Effort, which was cataloged in the 1908 book Sloops of the Hudson, and mentioned the reputation that the steamer James W. Baldwin had for collisions. Thankfully, we have in our collection the published articles of Captain William O. Benson, who just happens to recount that history! The article below is a verbatim transcription of his original article.

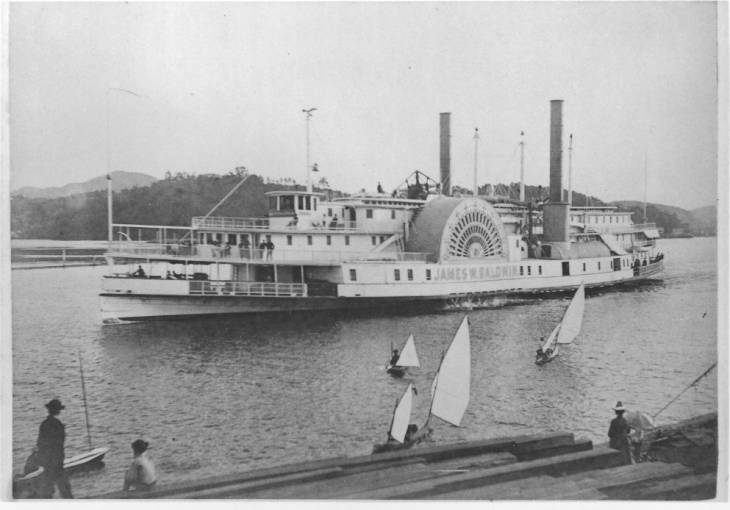

The ‘James W. Baldwin’ Becomes The ‘Central Hudson’

The Kingston Daily Freeman, Sun., Nov. 25, 1973 By CAPT. WM. O. BENSON The old Rondout to New York night boat “James W. Baldwin,” that linked Rondout and Kingston with the metropolis to the south longer than any other, had her share of mishaps. The ‘‘Baldwin” ran on the river during an era when sloops and schooners still plied the Hudson in great numbers. On one dark and hazy night, while making a landing at Marlborough, the steamer mistook a sloop’s lantern for a light on the dock. She hit the sloop, named “First Effort,” which sank in 50 feet of water and, which to this day, is still on the bottom of the river. Another time in 1904 on a black, rainy night off Esopus, the “Baldwin” collided with an ancient sloop named '‘Contrivance.” The sloop, carrying a load of brick, was 86-years-old and was sunk. The captain of the sloop, Calvin Delanoy, was drowned. On Wednesday, July 4, 1888, the “James W. Baldwin” was involved in an accident that subsequently led to the steamboat's name being changed to “Central Hudson.” On that holiday evening shortly after 8 p.m. on leaving her dock at Newburgh, a small steam launch carrying eight people crossed the steamboat's bow. Despite the steamer's frantic efforts to back down, it was too late to get the way off the “Baldwin.” The launch was hit amid-ships [sic] and immediately sank. Quick action by the “Baldwin's" crew saved six of the eight people in the launch. Of the two persons lost, one unfortunately happened to be Mrs. Benjamin B. Odell, Jr., whose husband would later become Governor of New York State and head of the steamboat company that years later was to acquire ownership of the “James W. Baldwin.” Of the accident itself, a coroner's jury later found the launch to be at fault and exonerated the men in the “Baldwin's” pilot house of blame. During the latter half of the 19th century, virtually every community of any size along the Hudson River was linked to New York by its own steamboat line. In 1899, the three independent steamboat companies serving Newburgh, Poughkeepsie and Kingston were consolidated into one company, the new company being named the Central Hudson Steamboat Company. One of the prime movers behind the consolidation and an officer of the new company was Benjamin B. Odell, Jr. of Newburgh, whose wife had been drowned in the “Baldwin” incident 11 years before. Since the “James W. Baldwin” was one of the two steamers of the Kingston line acquired in the merger, she came under the Odell ownership. In 1903, the “Baldwin” underwent a rebuilding which included new boilers and a dining room on the saloon deck forward. Allegedly as an aftermath of her tragic accident of July 4, 1888, the “James W. Baldwin” at this point was renamed “Central Hudson.” As a final irony, the Central Hudson Line built a new steamer in 1911 to replace the “James W. Baldwin,” now named “Central Hudson.” The new steamboat's name was “Benjamin B. Odell.” Back in the glory days of the “James W. Baldwin” on the Rondout run, the steamer, particularly on Saturdays, would have brushes with the “Mary Powell.“ Both steamboats were scheduled to arrive at Rondout on summer Saturday evenings at about the same time. Coming up off Esopus both boats would frequently be neck and neck with throttles wide open. The Chief Engineer of the “Baldwin“ would pace back and forth across the main deck commanding his firemen, “Don’t you dare let that steam pressure drop one ounce, or you can go ashore at Rondout for good!" Up in the pilot house of the “Baldwin,” the pilots would try and jockey for position and get on the west side of the channel so their steamer would be on the inside of the turn going around Esopus Meadows lighthouse. Sometimes the “Baldwin” would cut the Esopus lighthouse so short her port paddle wheel would stir up the mud. When they got off Sleightsburgh and if they had a good high tide, I understand they would sometimes cut inside the Rondout lighthouse —which at that time stood on the south side of the creek. Then, how the water would turn muddy! If they beat the “Powell” to Rondout Creek, the “Mary Powell” would have to lay out in the river and wait for the “Baldwin” to go in the creek and get turned around. At times like that, sometimes the crew of the “Baldwin” would take their sweet time turning and handling lines just to show the people waiting on the dock the “Baldwin” was on time landing, and the “Powell” would be late landing her passengers—sort of 19th century one upsmanship. As the first decade of the 20th century drew to a close, the career of the old “James W. Baldwin” also approached its end. During 1910, the Central Hudson Line contracted for a new steamboat, designed as a replacement for the “Baldwin.” The new steamer, the “Benjamin B. Odell” made her first trip into Rondout Creek on April 11, 1911, bringing to a close the 50 year service of the “Baldwin,” now named “Central Hudson”, on the Rondout run. In May of 1911, the “Central Hudson” was chartered by a company known as the Manhattan Line which had sprung up as an opposition line to the Hudson River Night Line running to Albany and Troy. The “Central Hudson“ was to run with the steamer “Kennebec,” an old Maine steamboat. On her trip down river on May 20, 1911 in heavy fog, the '‘Central Hudson” ran aground below Jones Point, opposite Peekskill. She was aground some 13 hours before getting off and continuing on to New York. On the very next trip up river, heavy with freight, the “Central Hudson“ grounded again, making the turn too quick before getting up to Gee’s Point at West Point. Unfortunately, she ran aground at high water. The Cornell tugboats “E. C. Baker” and "G. W. Decker” were sent down from Newburgh to try and pull her off. By the time they got there, however, the tide was ebbing and the captain of the “Decker” later told me the rods from her spars were getting slack in them, an indication she was hogging. The way her bow was aground, the tugboat captains thought if they pulled on her, at her age, and if she came off, the “Central Hudson” might sink in the deep water there before they could get her beached. The captain of the “Decker“ observed, “If they had had a Central Hudson Line crew on the old “Baldwin” like Amos Cooper and Abram Brooks, the accident would never have happened. Look at the hundreds of times those two men took her around there in years past without anything happening.” Finally, Merritt, Chapman and Scott, the marine salvagers, had to be hired to free the “Central Hudson.” After getting her afloat, it was found she was so badly strained, the old steamer would have to he retired. She was towed to Newburgh where she lay for nearly six months. On Nov. 15, 1911, the “Central Hudson,” or as she was better remembered as the “James W. Baldwin” was towed to the old steamboat graveyard at Port Amboy, N.J. and broken up. During her long career, the steamboat was commanded by a long line of well known Hudson River captains. The list included Captains Jacob H. Tremper, Jacob H. Tremper, Jr., Reuben H. Decker, Weston L. Dennis, Arthur Palmer, Zack Rossa and F. L. Simpson. For decades after she was gone, the old “James W. Baldwin” was remembered by steamboatmen and spoken of kindly—as the old side wheeler that after running between Kingston and New York for 50 years did not want to go off on a new route with a new crew.

If you enjoyed this history article, please consider donating to support the RiverWise project.

1 Comment

|

AuthorThis Captains' Log is kept by the captains and crew of Solaris and Apollonia and staff of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed