|

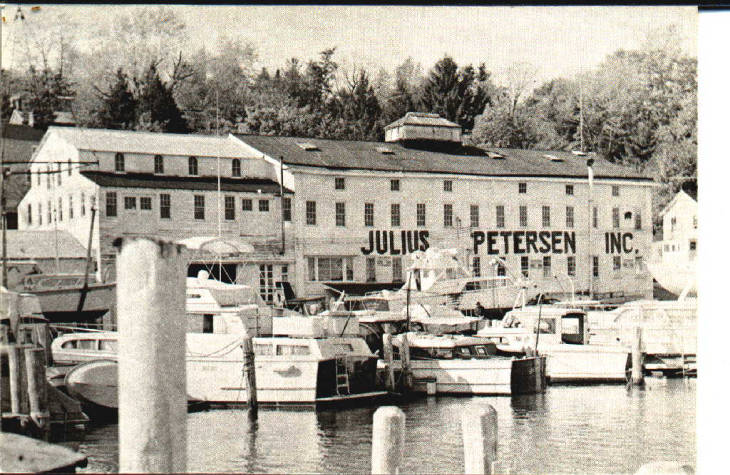

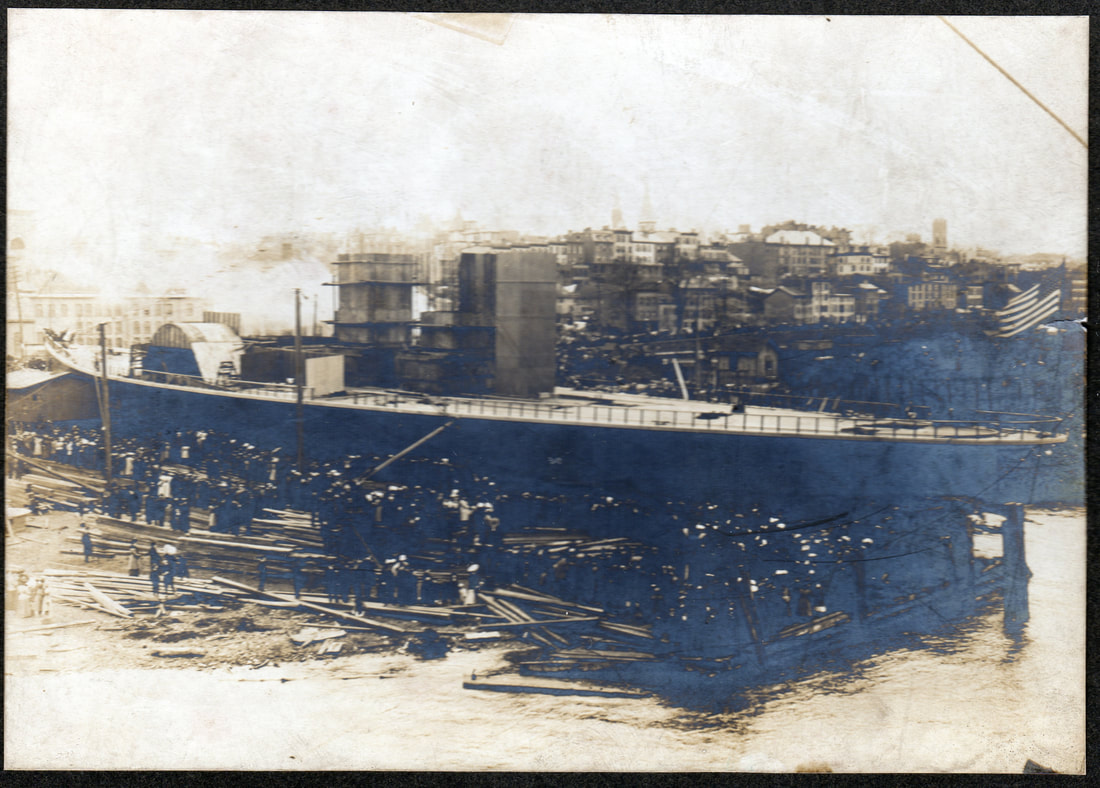

Nyack is located on the western shore of the "Tappan Zee" - an area of the Hudson River so wide that the Dutch referred to it as a "zee" or "sea." The remains of oyster middens at Nyack indicate it was used by the Lenape people as a popular fishing area. Settled by the Dutch in the 1640s, in the 19th century Nyack became an industrial hub, known for its quarries of red sandstone early in the century, and also for boatbuilding and shoe manufacturing. The North River Shipyard is one such boatbuilder that still remains today. Daniel Wolff has compiled a history of the yard, previously known as Peterson's Shipyard, which he has kindly shared with us.  Petersen's Shipyard - Foot of Van Houten - Upper Nyack, New York. This scenic shipyard has served as a government contractor of wooden submarine chasers during World War I, and crash boats similar to P. T.'s during World War II. Since that time the yard has been a repair and storage facility for recreational vessels. c. 1980. Nyack Library Local History Collection. A Partial History of the Upper Nyack Boatyard (now Petersen’s) from the 18th Century through World War 1 At the time of the American Revolution, the property that would become Petersen’s boatyard was co-owned by two large farms that stretched from the river up to the mountains in the west. The Sarvent family owned the southern farm of 70 acres; the Knapps had a 220 acres farm to the north. Both probably used the riverfront for transporting produce, building the boats they needed, and maintaining those boats -- hauling them up on the beach to scrape, caulk, and re-paint. Four years after the first road from Nyack to Piermont was built, on October 10, 1794, Benjamin Knapp, his wife, and David Pye sold 54 acres to Tunis Tallman and John Van Houten for 500 pounds. This included the northern half of what would become Petersen’s boatyard. Van Houten became sole owner by 1799. Around the same time, Phillip Sarvent sold the southern half of what would become Petersen’s Boatyard to Garret Graba. The early 1800’s marked the beginning of commercial boat building in the area. In 1804, the first market sloop was built in Nyack, Aurora, owned by Abram and Hallman Tallman and Peter Depew; Captain Meyers sailing her. Eleven years later, Nyack-builder Henry Gesner built the centerboard sloop, Advance, for Jeremiah Williamson. It was reputed to be “the first center-board boat on any size built in this country if not in the world....” Seeing the potential in the boat-building industry and the advantages of the Upper Nyack site, Johanes Van Houten secured the underwater rights off his landing from New York State in 1824. With “the Dock” beginning to prosper, Van Houten and his wife, Eleanor, began selling off small building lots surrounding it. By 1827, the Nyack turnpike was built inland, over the mountains from Nyack, and the Van Houtens started sub-dividing lots on the thoroughfare which is today called Broadway. By this time, the Van Houtens had purchased the south end of the yard from Graba, but they didn’t seem interested in running the entire acreage as a boatyard. Instead, in 1830, the Van Houtens sold John I Felter, a boat builder, the three-acre south portion of the yard including the underwater rights for $500. That year, Van Houten and Elijah Appleby paid a steamboat company $2000 to run the ferry Rockland between the Upper Nyack landing and New York City. They also agreed to build a 50-foot tow-boat to be part of the operation. The years between 1835 and the mid-1840’s were when the construction of Nyack sloops flourished. Over 30 would be built in that period. The prosperity was reflected in and around the Upper Nyack shipyards. The first marine railway for hauling and launching ships was built on Staten Island in 1830. Four years later, John Van Houten added this technological advance on the northern portion of the landing: the first such railways in Upper Nyack. The bustling complex included a blacksmith operation run by John Demarest who bought a building lot on Broadway from the Van Houtens in 1835. In 1837, the 22-year-old skipper of the sloop, M Lucretia, William Matthews, bought a lot “near the first turn from the dock” (on Van Houten Street). In 1839, John Felter added his own set of marine rails south of Van Houten’s; the two boatyards were, if not in competition, friendly adversaries. The census of 1840 shows a number of sailors living near the boatyard. John Wood with his wife and two infants had a house in the middle of Van Houten on the west side. Brace Redding, middle-aged, with his teenage son (also a sailor), wife and two daughters owned the third house up the east side of Van Houten from the docks. David Matthews, a sailor with a wife and son were in the next house downhill. John Demarest with three infants had a piece of property in the middle of the yet-to-be-named Ellen Street (behind his Broadway lot). And William Moore, a free colored man (who was a sailor) lived with his wife and daughter in the area, perhaps as renters. The most prolific local boat-builder of the era was James B Voris, located in Nyack. As the local paper would later report: “... most of the freighting along the Hudson River was done with schooners, and a majority of the vessels engaged in that traffic were constructed by [Voris]. This line of business proved a boon to many owners of woodland in this county, for Mr. Voris purchased nearly all the timber from them. Nyack at that time acquired a wide reputation for boat-building....” In 1844, John Van Houten deeded his land to his son, John, Jr. In 1847, the Sarvents sold John I Felter another small parcel of land to add to his boatyard south of the Van Houten’s. A year later, in 1848, John Van Houten, Jr. died intestate, his land going to his only daughter, Eleanor Tallman, wife of Tunis Tallman. By the 1850 census, Tunis S. Tallman’s net worth of $15,000 included the northern part of the boatyard with its ferry landing and a hotel, inherited through his wife. Residents near the boatyards included ship’s carpenters, blacksmiths, and “boatmen.” William Matthews, who had moved to New York City to run an ice business, returned to Nyack in 1850 to captain the ferry, John J Herrick, between Nyack and Tarrytown. Meanwhile, Sylvester Gesner of Nyack was building a 100-ton U.S. cutter, 65 feet long, in Nyack, two other vessels were “on the ways at upper landing,” and the keel of a NY steamer had been laid. The listing of the “Young Shipwrights Association of Nyack” in 1851 listed John W. and Robert Felter; Edward, William and Henry Perry; and Isaac Gesner. Robert Felter leased the southern boatyard in Upper Nyack from John Felter (meanwhile employing John W Felter!). That March 22, 1851, Robert Felter launched the “new and splendid sloop John Jones” in Upper Nyack: she was 75’ long with a 25’ beam and 5’ 10” hold, weighing 83 tons. Her mast was 86 feet tall, her boom 75 feet, and her bowsprit extended 34 feet from her night-heads. She required more than a thousand feet of canvas and was built for William D Reed of Verplanck’s Point. The launching, as recorded in a local Nyack paper, gives an idea of how such an event proceeded: “At one o’clock p.m., a large number of spectators had assembled to witness the imposing sight. A special invitation had been given to the mechanics of the other ship-yards in the neighborhood, who responded generally to the call, and by their presence and assistance, aided materially in the work. The tide rising slowly, and the many little preparations which are indispensable, seemed to tax the patience of some, until at last an unusual bustle was observed among the mechanics, and a noise almost deafening, proceeding from nearly fifty mauls announced that the time had arrived. After a few minutes, silence being again restored and an observation taken, the voice of the master builder was heard “let her go,” the spurshores were knocked away, the noble vessel responded at first by a graceful tremble, and then a perceptive motion which gradually increased with the distance, until the water of the noble Hudson received her on its bosom, and the loud huzza and cheering response announced to the crowd that the launch was over." That summer, the builder, R Felter, bought an Upper Nyack building lot “beginning with the New Road leading from Daniel M Clark’s store to the landing.” Clark’s store was at the NE corner of Castle Hts and Broadway, no doubt taking advantage of the travelers coming in on the ferry, as well as those using the turnpike inland. [By 1855, one Moses Leonard would combine Clark’s store lot with Felter’s, downhill towards the river, and build a large house at the top of lower Castle Heights, Northeast corner] The year after the triumphant launching of the 83-ton John Jones, Robert Felter built a 91 ton schooner, Norma, for Wm Cutter and H Anderson of Nyack. In the Upper Nyack boat-building competition, the south yard seemed to be winning. But by June, 1852, Robert Felter was “indebted to summary persons, and being in embarrassed circumstances” per a mortgage document of the time, had all his land, chattel, merchandise, etc. auctioned off to pay debts. This included his real estate on Clark’s Road (former name for lower Castle Heights) and his lease of the shipyard, due to expire in July of 1852. He also auctioned off a quarter-part share in the schooner Alferetta of New York and a half-part share in the schooner Genius of Nyack. A look at the inventory of Felter’s goods at the yard gives an idea of what was needed in a mid-19th century ship building operation: “... 302 feet of 6 inch timber, three 5 inch knees; 122 pieces of timber ... 800 lbs. of nails ... 66 lbs. red lead.... 2,200 feet of yellow pine ... 1600 lbs. of oakum ... 7 barrels of pitch ... 32 gallons turpentine ... 20 lbs. of putty ... 80 gallons of varnish ... 14,888 feet of 10 inch oak plank ... one boat, 2 grindstones....” After the bankruptcy, the southern yard reverted to John I Felter, who may have run it for a few years. But in 1856, John Clough of Coxsackie and Isaac Hallenbeck bought it as part of a Supreme Court of New York lawsuit. [Note that the riverfront land was bordered all around by quarries for Hudson River redstone: useful for building houses in the little marine-related village that had sprung up around the yard.] The troubles in Upper Nyack seemed to be personal, not a result of a downturn in boat construction. That same year, Nyack builder James B Voris finished the yacht Minnie for William H Thomas; she would go on to win that year’s race around Long Island. Six months after buying it, Clough and Hallenbeck sold their two-and-a-half acre boatyard (plus “railway premises”) to William H Dixon for $3000. A map from the time shows a 300-foot long/ 100-foot wide dock extending into the Hudson. At the edge of the river, the land was roughly 270 feet wide and ran back 225 feet to the “road to the landing.” That landing – the northern part of the property -- was still owned by Tunis S Tallman. Meanwhile, down in Nyack, James B. Voris had turned out a second yacht for William Thomas, the Zinga, which proved to be the fastest boat in the 1859-60 New York Yacht Club races. In the 1860 census, residents around the dock included ship carpenters, a cooper, a mason, a fireman on a steamboat, and “boatmen.” As the civil war began, the William Dixon and his wife sold the southern half of the boatyard to Caroline Dixon (presumably a daughter) of Nyack for the same $3000 they’d paid. Tunis S Tallman died in 1864, towards the end of the Civil War. That spring, his widow Eleanor Tallman sold the northern yard (“all that Hotel and Dock and railway premises” plus 300’ into the river) to James B Voorhis, 44 years old, for $8,000 plus a $2,000 mortgage. The northern yard ran 380 feet along the water; at its south-west corner, it only consisted of 66 feet of land jutting out into the river, but Voorhis’ property extended another 300’ underwater. Three weeks earlier, Caroline Dixon had sold the two-and-a-half acres of the southern yard to John W Felter of Upper Nyack for $4500. This was returning the yard to the family that had been there for the previous thirty years. Felter and his wife bought the house at what is now 10 Castle Hts. In 1868, John I Felter, boat builder and father of John W, died, age 71. His son, 38, couldn’t maintain the yard and sold it to William Dickey. The following spring, he had to sell the house at 10 Castle Hts to William Jersey (for $3000). In 1870, (the year the railroad spur reached Nyack) the census still listed John W Felter as a ship carpenter, his son as a worker in a sail factory. James B. Voorhis, a 60-year-old ship carpenter, owned $8000 worth of real estate. Through a sheriff’s sale in August of the following year, Voorhis picked up the southern yard, so that for the first time in a century the entire boatyard now had a single owner. In 1872, a John W. Voorhis (age 39, his relationship to the owner of the yard unclear) is building 100 and 115-foot schooners in Upper Nyack, and the next year he launches a 300-ton three-master and a 400-ton schooner. In 1874, James B Voorhis and his wife, Rachel, sold the boatyard (for one dollar) to his son, James P Voorhis. The 1875 census reflects the changes towards industrialism in the Nyack area. Many of the inhabitants worked at the local shoe factories. In Upper Nyack, James B Voorhis, 64, listed himself as a carpenter. Up the street was 46-year old Robert Kennier, captain of a schooner; Kennier’s two sons were sailors. Also in the immediate neighborhood of the boatyard, Tunis Kent, 56, was a ferryboat pilot, and Moses Wyman and his son were both carpenters. So were John Perry and Oswith Perry. The estimated daily wage for a ship carpenter in 1875 was $3.25, compared to a shoemaker who got $2, or a blacksmith who got $3 a day. On July 20, 1875, the widow Eleanor Tallman sold James P Voorhis the underwater land by the boatyard for $100. Voorhis lived near the river on the southernmost part of his property. He also owned the store at the site of the present city hall (Castle Hts and Broadway). 1877 marked an economic collapse in Nyack; James B Voorhis retired from shipbuilding, age 67. Two years later, J.W(?) Voorhis was hurt at his Upper Nyack yard. There was apparently still a ferry landing at the yard because the Union Steamboat Company was paying taxes on $280,000 personal property in Upper Nyack but owned no real estate. In 1880, Moses Wyman, a ship’s carpenter and his son, Ebenezer, in the same trade, lived at what is now 12 Castle Hts. John Rose, a ship’s carpenter, lived at the corner of Perry Lane and Broadway with a brother who plied the same trade. The Perry family included John, 59, a ship carpenter, his brother Daniel, the same, and William, a sailor. John W Felter, at 14 Castle Hts was also a ship’s carpenter as was his 26 year-old son, Ino. Tunis Kent, on Ellen Street, was still a steamboat pilot and his neighbor, William Williams was a steamboat engineer. James Voorhis was 69 by now, and his two lots on river had declined in value and were worth a total of $7000. Peter Voorhis, 43, was also on the river building boats. A July 22, 1882 edition of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly included an etching of the “dome steamer” Meteor being built in Nyack. The double-chimneyed vessel is in the docks with Hook Mountain clearly visible in the background. In 1883, James P Voorhis was launching yachts at Upper Nyack. The community had turned more upper crust. The Schuller family donated money for the city hall and firehouse. In May of 1889, Voorhis was, according to the local paper, “talking about going to South America.” A divorce suit between Voris and his wife had her accusing him of striking and beating her and forcing her out of her bed at night, as well as using profane language; he denied everything, arguing: “[H]e would have been legally and morally justified in inflicting personal chastisement and moderate violence upon her in consequence of her language and manner of treatment of him ... that she has been in the habit of leaving defendant and young children and remaining away from one to fifteen consecutive days; that she had threatened to poison defendant, and that she had got into the habit of drinking beer and other stimulants to excess.” A month earlier, Voorhis had turned over the management of the yard to R.B. Rodenmond of Tompkins Cove. Rodenmond needed a yard that could handle bigger boats. An article at the time described the yard: “There are three marine railways on which to operate, besides the yards are better equipped for doing work than any place along the Hudson. In connection with this a large saw mill has also been purchased near the yards which has all the latest appliances for sawing out timber for vessels.” Rodenmond announced in May of 1889 that three vessels were being built, more coming; all men at work and more needed. As the local Evening Journal put it; “The present season at the Nyack shipyards is characterized by a remarkable degree of activity, and from present indications the coming Summer will bring a prosperity unequaled in many years past. “The Nyack boat-builders long ago acquired a reputation for first-class workmanship in their line, and one of the proudest facts which the Journal can announce is that this reputation is being splendidly maintained.” By 1890, the Upper Nyack population was 668. Moses and Charles Wyman were still ship carpenters and living at 12 Castle Heights, John Perry was also a ship’s carpenter along with John W Voorhis, but William Voorhis listed himself as a piano maker. Rodenmond rented the M.B. Demarest house on Castle Hts. By 1891, the James P Voorhis divorce case had ended in a hung jury and Mr. Voorhis was running a saloon in Harlem. In October of the next year, James B Voorhis (the father) died. He was nearly 82 years old and was described as having “built more sail vessels than any other builder along the river.” But since his time, the yard had run down considerably, and Rodenmond apparently couldn’t make a go of it despite prosperity in the “Roaring ‘90’s.” On May 18, 1893 Samuel Ayres bought the boatyard (hotel, dock and railroad) at public auction at the Hotel St. George. The yard employed 8 men; Ayres brought 15 more form his South Brooklyn boiler plant, which he had operated for the past 40 years. Ayres had purchased the yard because he’d recently acquired a farm in West Hempstead and wanted his work to be closer to home. In Brooklyn, Ayres had built boats for “Commodore Gerry, the Vanderbilts, and other prominent men in the city.” He set to work dredging the basin to 10’, adding a 400’ dock, as well as building a 100 x 50 foot three-story frame building. Two-thirds of this building still stands at the center of the present boatyard. Cost was estimated at $10,000 for the entire re-fitting. The operation would be called Ayres and Son. The “Son” was James C Ayres who, on October 16, 1899, bought the Youmans family house at 8 Castle Hts for $1600. By 1900, Upper Nyack’s population was 516, a decline. In 1905, John W Felter was still listed as a boat builder, age 72, Charles Wyman was a 56-year old boat builder, Andrew Kennier was a 47-year-old boat builder, James Ayres, 36, was a boat builder with his wife Alice. But James Ayres died that November 23 of apoplexy and a cerebral hemorrhage. The obituary listed him as having been 12 years in Upper Nyack, which means he lived in the area before his father bought the boatyard. The next dozen years, the yard remained in the possession of Alice Ayres who apparently kept it going, although it was once again on a decline. In May, 1917, she sold to International Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering to produce subchasers for WWI. Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, commissioned designs for an effective antisubmarine vessel, which could be quickly built in small boatyards by civilians already skilled in wooden boat building. The winning design was for an 110-foot long vessel, with 15-foot-6-inch beam and drawing 4-foot-6-inches. Each subchaser had three 220 horsepower engines and could go at 17 knots with a 1000-mile cruising range. The Government wanted 500 of these “swatters” built in the first year, or roughly one a week. In Nyack, the new owners of the yard planned to meet this demand by employing between 200 and 500 men with a $12,000 weekly payroll. The first subchaser was launched in the old boatyard on December 15, 1917. The paper reported that it made the 40-mile trip from Upper Nyack to the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 2 hours and 10 minutes.  Ten rescue boats in Hudson River, Upper Nyack, were built at the Julius Petersen Boatyard. This is written on the back: "Feb. 1945, Julius Petersen, Inc. Aircraft Rescue Boats; Given to Edward B. Leahey, MD, South Nyack in 1980 by Craig Carle, owner of Petersen Shipyard. 8/14/96 EBL MD." Nyack Library Local History Collection. AuthorDaniel Wolff is a journalist, an author of nonfiction books, a Grammy-nominated music writer, a filmmaker, a song lyricist, and a poet. If you enjoyed this history article, please consider a donation to support the RiverWise project:

1 Comment

Newburgh’s Shipbuilding Heritage in the Days of Wooden Ships & Sail By William duBarry Thomas (originally published in the Pilot Log, 2000) Newburgh was the shipbuilding center of the mid-Hudson region for well over a century and a half. Although the earliest accomplishments of local shipwrights are clouded by the passage of time, sailing vessels were constructed during the colonial days by such men as George Gardner, Jason Rogers, Richard Hill and William Seymour along the village’s waterfront, which extended approximately from the foot of present day Washington Street north to South Street. Strategically well placed at the southernmost point before one entered the Hudson Highlands, Newburgh became the river transportation center, serving the inland towns and village to the north and west. The Highlands form a magnificent scenic delight in the mid-Hudson region, but in the pre-railroad era they were decidedly unfriendly to the movement of goods and people. In short, the Hudson became a marine highway which connected upstate regions to the Metropolis at its mouth. A significant freighting business therefore developed at Newburgh, and, in addition, the village became one of the region’s bases for the whaling industry. Both of these undertakings required sailing vessels, and with forests of suitable timber nearby, the local shipbuilders were well placed to support the burgeoning commerce on the river. Much of this changed with the introduction of the steamboat in the summer of 1807, when Robert Fulton’s North River Steamboat made her first trip to Albany. It was inevitable that steam should be adopted almost universally on America’s waterways. The earliest steamboat built at Newburgh is reputed to have been the side-wheel ferry Gold Hunter, constructed in 1836 for the ferry between Newburgh and Fishkill Landing. We are not certain of the identity of her builder, but her appearance coincided with the start of local shipbuilding by the dynasty which dominated that industry locally for 110 years – Thomas S. Marvel; his son of the same name; and his grandson, Harry A. Marvel. The shipbuilding activities of these three generations of the Marvel family encompassed the period from 1836 until 1946, when Harry Marvel retired from business. Although their activity was not continuous throughout this period, the reputations of these men as master shipbuilders survived the periodic and all too frequent ups and downs that have always plagued this industry. The senior Thomas Marvel, born in Newport, Rhode Island in 1808, served his apprenticeship as a shipwright with Isaac Webb, a well known shipbuilder in New York. Around 1836, he moved to Newburgh and commenced building small wooden sailing vessels, sloops, schooners and the occasional brig or half-brig, near the foot of Little Ann Street, later moving to the foot of Kemp Street (no longer in existence). Among the vessels he built was a Hudson River sloop launched in the spring of 1847 for Hiram Travis, of Peekskill. Travis elected to name his vessel Thomas S. Marvel, a name she carried at least until she was converted to a barge in 1890. An unidentified 160-foot steamboat was built at the Marvel yard in 1853. She was described by the local press as a “new and splendid propeller built for parties in New York.” Possibly the first steamboat built by Thomas Marvel, this vessel was important for another reason – she was propelled by a double-cylinder oscillating engine built on the Wolff, or high-and-low pressure principle. Ernest Wolff had patented his design in 1834, utilizing the multiple expansion of steam to improve the efficiency of the engine. The Wolff engine was a rudimentary forerunner of the compound engine, which did not appear for another two decades. The younger Thomas joined his father in 1847, at the age of 13. The young man, who was born in 1834 in New York, was entrusted with building a steamboat hull in 1854. This was a classic case of on-the-job training, for the boat was entirely young Tom’s responsibility. She is believed to have been Mohawk Chief, for service on the eastern end of the Erie Canal. The 85-3/95 ton Mohawk Chief, 86 feet in length, was described in her first enrollment document as a “square-sterned steam propeller, round tuck, no galleries and no figurehead.” The dry, archaic language of vessel documentation was hardly accurate, for her builder’s half model, still in existence, proves that she was a handsomely crafted little ship with a graceful bow and fine lines aft. The elder Thomas Marvel retired from shipbuilding at Newburgh sometime before 1860. He later built some additional vessels elsewhere, including the schooner Amos Briggs at Cornwall. He may have commanded sailing vessels on the river in his later years, for he was referred to from time to time as “Captain Marvel.” By the mid-1850s, the younger Thomas Marvel had become a thoroughly professional shipwright, and undertook the management of the yard’s operation, at first as the sole owner and later in partnership with George F. Riley, a local shipwright. The partnership continued until Marvel volunteered for service in the Union Army almost immediately after the start of the Civil War in April 1861. He served as Captain of Company A of the 56th Regiment until he was mustered out due to illness in August 1862. He returned to Newburgh, but shortly afterwards moved to Port Richmond, Staten Island, where he built sailing vessels and at least one steamboat. A two-year period in the late 1860s saw him constructing sailing craft on the Choptank River at Denton, Maryland, after which he returned to Port Richmond. During the Civil War and for a few years afterwards, George Riley continued a modest shipbuilding business at Newburgh, later with Adam Bulman as a partner. They went their separate ways in the late 1860s, and Bulman teamed with Joel W. Brown in 1871, doing business as Bulman & Brown. For the next eight years, they build ships in a yard south of the foot of Washington Street, where they turned out tugs, schooners and barges. Their output of tugs consisted of James Bigler, Manhattan, A.C. Cheney and George L. Garlick, and their most prominent sailing vessels were the schooners Peter C. Schultz (332 tons) and Henry Pl Havens (300 tons), both launched in 1874. Another source of business was the brick-making industry, which required deck barges to move its products to the New York market. Nearly all of the 19th century New York City was built of Hudson River brick, and the brick yards on both shores of Newburgh Bay contributed to this enormous undertaking. In 1872 alone, Bulman & Brown built at least five brick barges for various local manufacturers. Vessel repair went hand in hand with construction. Bulman & Brown built and operated what might have been the first floating dry dock at Newburgh. In 1879, the firm moved to Jersey City, New Jersey, and Newburgh lost a valuable asset. This prompted Homer Ramsdell, the local entrepreneurial steamboat owner, to finance the construction of a marine railway located at the foot of South William Street. Ramsdell, whose interests included the ferry to Fishkill landing and the Newburgh and New York Railroad, as well as his line of steamboats to New York, wanted to be sure that his fleet could be hauled out and repaired locally without the need for a trip to a New York repair yard. The mid-1870s, which marked the end of the wooden ship era at Newburgh and the start of the age of iron and steel, brings us to the close of this portion of the sketch of the area’s shipbuilding. From this time onward, the local scene would change radically. The firm of Ward, Stanton & Company, successors to Stanton & Mallery, a local manufacturer of machinery for sugar mills and other shoreside activities, entered shipbuilding and persuaded Thomas S. Marvel to join the company in 1877 to manage its shipyard. Newburgh, which had been incorporated as a city in 1865, was about the enter the major league in ship construction. Here is a full list of all the boats built by Marvel Shipyard over the years.

If you enjoyed this history article, please consider donating to support the RiverWise project. In the 18th century, Poughkeepsie was a main port on the Hudson River and was involved in shipbuilding. During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress ordered two sea-going frigates to be built at Poughkeepsie as part of legislation to build 13 frigates throughout the colonies. Three-masted frigates were the backbone of many navies although smaller than more heavily gunned ships of the line. The Act of December 13, 1775 authorized (3) 24 gun frigates, (5) 28 gun frigates and (5) 32 gun frigates in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire and Connecticut. Politics were an important factor in distributing these contracts among the former colonies. The Poughkeepsie frigates Congress (28 guns) and Montgomery (24 guns) were begun in 1776 by Lancaster Burling and launched unfinished into the Hudson in October of the same year. There was no urgency to complete them given the British control of New York City and blocked access to the sea. Men and materiel were diverted to more strategic locations including Lake Champlain. The fitting out of the two frigates apparently languished. The frigates are believed to have been approximately 120 ft and 126 ft in length and 32 ft to 34 ft in beam. Based on surviving plans for a similar 28 gun frigate, the Congress featured a largely open gun deck with raised quarterdeck and forecastle. She was to have been armed with (26) 12 pounders and (2) 6 pounders. The Montgomery, named for the fallen general Richard Montgomery who died in the assault on Quebec in 1775, was to have been armed with (24) 9 pounders. Slightly shorter, her basic configuration was likely similar to that of the Congress. During the British advance on forts Montgomery and Clinton in 1777, the two unfinished frigates were rushed down the Hudson to support the American defenses. They likely carried partial rigs and may not have carried their full complement of guns. The forts were attacked from the rear and both fell. Unable to retreat back up the river due to tide and wind, the Americans burned the ships and escaped in small boats in order to prevent the capture of the valuable frigates. To date, no evidence of either ship has been found in the river bottom leading to some speculation that they may not have sunk and that their salvage went unnoticed after the battle. No images of either frigate survives, likely becacuse they remained unfinished. But other frigates, including the USS Confederacy, pictured here in a painting by William Nowland Van Powell, were completed, though the Confederacy also did not survive the Revolution. In fact, almost all of the frigates of the Continental Navy did not survive, either due to damage in battle, capture, or because they were sunk to avoid capture, like the Congress and Montgomery. you enjoyed this history article, please consider donating to support the RiverWise project.

|

AuthorThis Captains' Log is kept by the captains and crew of Solaris and Apollonia and staff of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed