|

For immediate release:

RiverWise Fleet Sail Around Statue of Liberty Hudson River Maritime Museum Partners with Classic Harbor Line Kingston, NY – As part of the RiverWise project, the Hudson River Maritime Museum is pleased to announce that the museum’s solar-powered boat Solaris and carbon-neutral Schooner Apollonia will be conducting a fleet sail to the Statue of Liberty with five vessels from the Classic Harbor Line on Thursday, August 20, 2020 at 6:30 p.m. Carbon-neutral vessels Solaris, a 100% solar-powered boat from the Hudson River Maritime Museum, and Schooner Apollonia will lead this fleet sail, joined by New York City's own Classic Harbor Line with its majestic tall ship schooners America 2.0 and Adirondack, as well as their vintage replica commuter yachts Manhattan II, Kingston and Full Moon. Classic Harbor Line's fleet, which is built in Albany, NY, by Scarano Boat Building, is the embodiment of one of the RiverWise themes for this year: local boatbuilding. This fleet of seven unique vessels against the backdrop of the Statue of Liberty near sunset offers a stunning photographic opportunity. Vessels are expected to arrive at the Statue of Liberty around 6:30 PM and Battery Park by 7:30 PM. The public is encouraged to view the vessels from shore. Battery Park is the best viewing area. Or, tickets are available for the trip aboard Classic Harbor Lines vessels. For ticket information, please visit www.sail-nyc.com. Daily updates of the RiverWise: South Hudson Voyage, including live video, blog posts, and links, will be posted on the Hudson River Maritime Museum’s Facebook page and Instagram account. The public is invited to like the museum’s pages to be notified of updates. Daily updates will also be posted at the end of the day, along with additional history articles, on the RiverWise website’s Captains’ Log at www.hudsonriverwise.org/log. The South Hudson Voyage is part of a broader effort the museum calls “RiverWise.” During the voyage museum staff and crew will collect film footage, conduct interviews, and produce short films, photos, and social media content to teach the general public about the Hudson River and allow them to experience it in real-time, as the crew does, from the comfort of their own homes. After the voyage, museum staff will process the hundreds of hours of film footage collected on both voyages and begin to create short documentary films about the Hudson River and its history, with emphasis on the four themes highlighted this year – lighthouses, shipbuilding, towing, and sail freight. The museum is seeking donations to support both the voyage and the documentary films. The South Hudson Voyage is funded by individual donations and sponsorships. Mid-Hudson Federal Credit Union has sponsored in part Solaris, Apollonia, and the documentary films on Hudson River shipbuilding. The Daley Family Foundation has sponsored Apollonia. General support comes from the many individuals who have donated to the by-the-mile voyage campaign through PledgeIt. The North Hudson Voyage was sponsored in part by the Phelan Family Foundation, Ann Loeding, David Eaton, and the many individuals who donated to the PledgeIt campaign. Additional funding for both campaigns has been provided by the Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area. The museum is still seeking sponsorships to help cover the costs of the South Hudson Voyage as well as this year’s four documentary film themes – lighthouses, tugboats and towing, shipbuilding, and sail freight. If you would like to support the South Hudson Voyage and the museum’s documentary films, please visit www.hudsonriverwise.org/support for more information on sponsorship and donation opportunities. ### About the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Located along the historic Rondout Creek in downtown Kingston, N.Y., the Hudson River Maritime Museum is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization dedicated to the preservation and interpretation of the maritime history of the Hudson River, its tributaries, and related industries. HRMM opened the Wooden Boat School in 2016 and the Sailing & Rowing School in 2017. In 2019 the museum launched the 100% solar-powered tour boat Solaris. www.hrmm.org About Solaris. Solaris was built by the Hudson River Maritime Museum’s restoration crew under the direction of Jim Kricker. Solaris is the only US Coast Guard-approved 100% solar-powered passenger vessel in the United States. It does not plug in. Designed by marine architect Dave Gerr from a concept developed by David Borton, owner of Sustainable Energy, Solaris is commercial in design, meeting all U.S. Coast Guard regulations for commercial passenger-carrying vessels. www.hrmm.org/meet-solaris About the Schooner Apollonia. The Apollonia is the Hudson Valley’s largest carbon-neutral merchant vessel. Powered by the wind and used vegetable oil, Apollonia can transport her cargo sustainably. This mission-driven, for-profit business has a transparent and reproducible business model - to provide carbon-neutral transportation for shelf-stable local foods and products. Connecting the traditions of slow food, fair trade, and carbon neutrality, we will inspire and train a new generation of Hudson River stewards and create green living-wage jobs in the growing river-based economy. www.schoonerapollonia.com

1 Comment

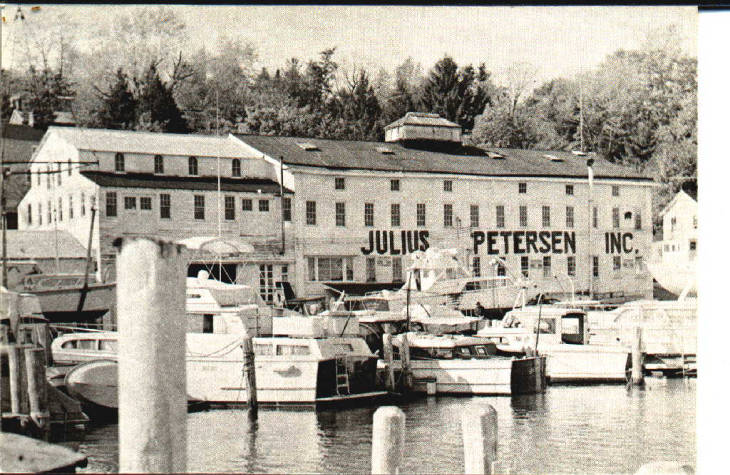

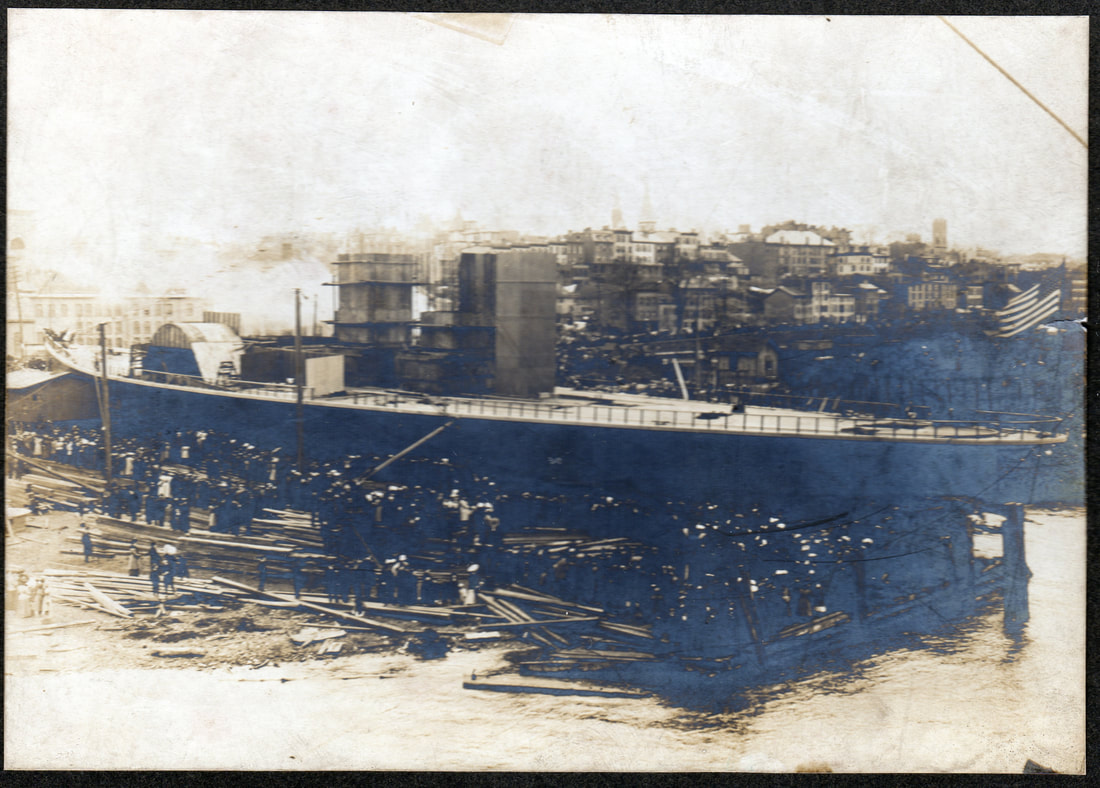

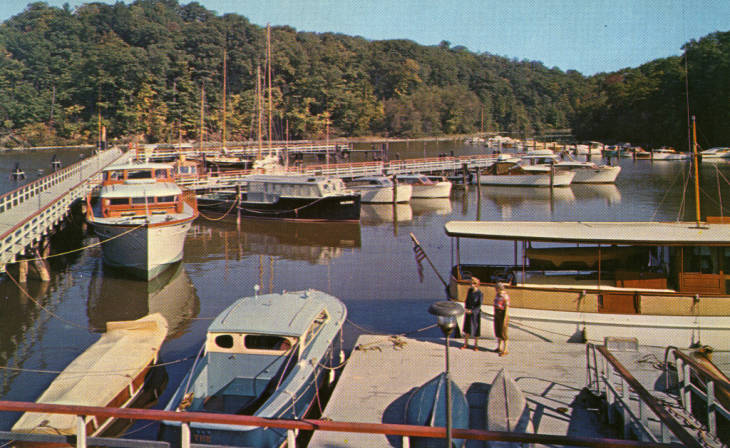

Nyack is located on the western shore of the "Tappan Zee" - an area of the Hudson River so wide that the Dutch referred to it as a "zee" or "sea." The remains of oyster middens at Nyack indicate it was used by the Lenape people as a popular fishing area. Settled by the Dutch in the 1640s, in the 19th century Nyack became an industrial hub, known for its quarries of red sandstone early in the century, and also for boatbuilding and shoe manufacturing. The North River Shipyard is one such boatbuilder that still remains today. Daniel Wolff has compiled a history of the yard, previously known as Peterson's Shipyard, which he has kindly shared with us.  Petersen's Shipyard - Foot of Van Houten - Upper Nyack, New York. This scenic shipyard has served as a government contractor of wooden submarine chasers during World War I, and crash boats similar to P. T.'s during World War II. Since that time the yard has been a repair and storage facility for recreational vessels. c. 1980. Nyack Library Local History Collection. A Partial History of the Upper Nyack Boatyard (now Petersen’s) from the 18th Century through World War 1 At the time of the American Revolution, the property that would become Petersen’s boatyard was co-owned by two large farms that stretched from the river up to the mountains in the west. The Sarvent family owned the southern farm of 70 acres; the Knapps had a 220 acres farm to the north. Both probably used the riverfront for transporting produce, building the boats they needed, and maintaining those boats -- hauling them up on the beach to scrape, caulk, and re-paint. Four years after the first road from Nyack to Piermont was built, on October 10, 1794, Benjamin Knapp, his wife, and David Pye sold 54 acres to Tunis Tallman and John Van Houten for 500 pounds. This included the northern half of what would become Petersen’s boatyard. Van Houten became sole owner by 1799. Around the same time, Phillip Sarvent sold the southern half of what would become Petersen’s Boatyard to Garret Graba. The early 1800’s marked the beginning of commercial boat building in the area. In 1804, the first market sloop was built in Nyack, Aurora, owned by Abram and Hallman Tallman and Peter Depew; Captain Meyers sailing her. Eleven years later, Nyack-builder Henry Gesner built the centerboard sloop, Advance, for Jeremiah Williamson. It was reputed to be “the first center-board boat on any size built in this country if not in the world....” Seeing the potential in the boat-building industry and the advantages of the Upper Nyack site, Johanes Van Houten secured the underwater rights off his landing from New York State in 1824. With “the Dock” beginning to prosper, Van Houten and his wife, Eleanor, began selling off small building lots surrounding it. By 1827, the Nyack turnpike was built inland, over the mountains from Nyack, and the Van Houtens started sub-dividing lots on the thoroughfare which is today called Broadway. By this time, the Van Houtens had purchased the south end of the yard from Graba, but they didn’t seem interested in running the entire acreage as a boatyard. Instead, in 1830, the Van Houtens sold John I Felter, a boat builder, the three-acre south portion of the yard including the underwater rights for $500. That year, Van Houten and Elijah Appleby paid a steamboat company $2000 to run the ferry Rockland between the Upper Nyack landing and New York City. They also agreed to build a 50-foot tow-boat to be part of the operation. The years between 1835 and the mid-1840’s were when the construction of Nyack sloops flourished. Over 30 would be built in that period. The prosperity was reflected in and around the Upper Nyack shipyards. The first marine railway for hauling and launching ships was built on Staten Island in 1830. Four years later, John Van Houten added this technological advance on the northern portion of the landing: the first such railways in Upper Nyack. The bustling complex included a blacksmith operation run by John Demarest who bought a building lot on Broadway from the Van Houtens in 1835. In 1837, the 22-year-old skipper of the sloop, M Lucretia, William Matthews, bought a lot “near the first turn from the dock” (on Van Houten Street). In 1839, John Felter added his own set of marine rails south of Van Houten’s; the two boatyards were, if not in competition, friendly adversaries. The census of 1840 shows a number of sailors living near the boatyard. John Wood with his wife and two infants had a house in the middle of Van Houten on the west side. Brace Redding, middle-aged, with his teenage son (also a sailor), wife and two daughters owned the third house up the east side of Van Houten from the docks. David Matthews, a sailor with a wife and son were in the next house downhill. John Demarest with three infants had a piece of property in the middle of the yet-to-be-named Ellen Street (behind his Broadway lot). And William Moore, a free colored man (who was a sailor) lived with his wife and daughter in the area, perhaps as renters. The most prolific local boat-builder of the era was James B Voris, located in Nyack. As the local paper would later report: “... most of the freighting along the Hudson River was done with schooners, and a majority of the vessels engaged in that traffic were constructed by [Voris]. This line of business proved a boon to many owners of woodland in this county, for Mr. Voris purchased nearly all the timber from them. Nyack at that time acquired a wide reputation for boat-building....” In 1844, John Van Houten deeded his land to his son, John, Jr. In 1847, the Sarvents sold John I Felter another small parcel of land to add to his boatyard south of the Van Houten’s. A year later, in 1848, John Van Houten, Jr. died intestate, his land going to his only daughter, Eleanor Tallman, wife of Tunis Tallman. By the 1850 census, Tunis S. Tallman’s net worth of $15,000 included the northern part of the boatyard with its ferry landing and a hotel, inherited through his wife. Residents near the boatyards included ship’s carpenters, blacksmiths, and “boatmen.” William Matthews, who had moved to New York City to run an ice business, returned to Nyack in 1850 to captain the ferry, John J Herrick, between Nyack and Tarrytown. Meanwhile, Sylvester Gesner of Nyack was building a 100-ton U.S. cutter, 65 feet long, in Nyack, two other vessels were “on the ways at upper landing,” and the keel of a NY steamer had been laid. The listing of the “Young Shipwrights Association of Nyack” in 1851 listed John W. and Robert Felter; Edward, William and Henry Perry; and Isaac Gesner. Robert Felter leased the southern boatyard in Upper Nyack from John Felter (meanwhile employing John W Felter!). That March 22, 1851, Robert Felter launched the “new and splendid sloop John Jones” in Upper Nyack: she was 75’ long with a 25’ beam and 5’ 10” hold, weighing 83 tons. Her mast was 86 feet tall, her boom 75 feet, and her bowsprit extended 34 feet from her night-heads. She required more than a thousand feet of canvas and was built for William D Reed of Verplanck’s Point. The launching, as recorded in a local Nyack paper, gives an idea of how such an event proceeded: “At one o’clock p.m., a large number of spectators had assembled to witness the imposing sight. A special invitation had been given to the mechanics of the other ship-yards in the neighborhood, who responded generally to the call, and by their presence and assistance, aided materially in the work. The tide rising slowly, and the many little preparations which are indispensable, seemed to tax the patience of some, until at last an unusual bustle was observed among the mechanics, and a noise almost deafening, proceeding from nearly fifty mauls announced that the time had arrived. After a few minutes, silence being again restored and an observation taken, the voice of the master builder was heard “let her go,” the spurshores were knocked away, the noble vessel responded at first by a graceful tremble, and then a perceptive motion which gradually increased with the distance, until the water of the noble Hudson received her on its bosom, and the loud huzza and cheering response announced to the crowd that the launch was over." That summer, the builder, R Felter, bought an Upper Nyack building lot “beginning with the New Road leading from Daniel M Clark’s store to the landing.” Clark’s store was at the NE corner of Castle Hts and Broadway, no doubt taking advantage of the travelers coming in on the ferry, as well as those using the turnpike inland. [By 1855, one Moses Leonard would combine Clark’s store lot with Felter’s, downhill towards the river, and build a large house at the top of lower Castle Heights, Northeast corner] The year after the triumphant launching of the 83-ton John Jones, Robert Felter built a 91 ton schooner, Norma, for Wm Cutter and H Anderson of Nyack. In the Upper Nyack boat-building competition, the south yard seemed to be winning. But by June, 1852, Robert Felter was “indebted to summary persons, and being in embarrassed circumstances” per a mortgage document of the time, had all his land, chattel, merchandise, etc. auctioned off to pay debts. This included his real estate on Clark’s Road (former name for lower Castle Heights) and his lease of the shipyard, due to expire in July of 1852. He also auctioned off a quarter-part share in the schooner Alferetta of New York and a half-part share in the schooner Genius of Nyack. A look at the inventory of Felter’s goods at the yard gives an idea of what was needed in a mid-19th century ship building operation: “... 302 feet of 6 inch timber, three 5 inch knees; 122 pieces of timber ... 800 lbs. of nails ... 66 lbs. red lead.... 2,200 feet of yellow pine ... 1600 lbs. of oakum ... 7 barrels of pitch ... 32 gallons turpentine ... 20 lbs. of putty ... 80 gallons of varnish ... 14,888 feet of 10 inch oak plank ... one boat, 2 grindstones....” After the bankruptcy, the southern yard reverted to John I Felter, who may have run it for a few years. But in 1856, John Clough of Coxsackie and Isaac Hallenbeck bought it as part of a Supreme Court of New York lawsuit. [Note that the riverfront land was bordered all around by quarries for Hudson River redstone: useful for building houses in the little marine-related village that had sprung up around the yard.] The troubles in Upper Nyack seemed to be personal, not a result of a downturn in boat construction. That same year, Nyack builder James B Voris finished the yacht Minnie for William H Thomas; she would go on to win that year’s race around Long Island. Six months after buying it, Clough and Hallenbeck sold their two-and-a-half acre boatyard (plus “railway premises”) to William H Dixon for $3000. A map from the time shows a 300-foot long/ 100-foot wide dock extending into the Hudson. At the edge of the river, the land was roughly 270 feet wide and ran back 225 feet to the “road to the landing.” That landing – the northern part of the property -- was still owned by Tunis S Tallman. Meanwhile, down in Nyack, James B. Voris had turned out a second yacht for William Thomas, the Zinga, which proved to be the fastest boat in the 1859-60 New York Yacht Club races. In the 1860 census, residents around the dock included ship carpenters, a cooper, a mason, a fireman on a steamboat, and “boatmen.” As the civil war began, the William Dixon and his wife sold the southern half of the boatyard to Caroline Dixon (presumably a daughter) of Nyack for the same $3000 they’d paid. Tunis S Tallman died in 1864, towards the end of the Civil War. That spring, his widow Eleanor Tallman sold the northern yard (“all that Hotel and Dock and railway premises” plus 300’ into the river) to James B Voorhis, 44 years old, for $8,000 plus a $2,000 mortgage. The northern yard ran 380 feet along the water; at its south-west corner, it only consisted of 66 feet of land jutting out into the river, but Voorhis’ property extended another 300’ underwater. Three weeks earlier, Caroline Dixon had sold the two-and-a-half acres of the southern yard to John W Felter of Upper Nyack for $4500. This was returning the yard to the family that had been there for the previous thirty years. Felter and his wife bought the house at what is now 10 Castle Hts. In 1868, John I Felter, boat builder and father of John W, died, age 71. His son, 38, couldn’t maintain the yard and sold it to William Dickey. The following spring, he had to sell the house at 10 Castle Hts to William Jersey (for $3000). In 1870, (the year the railroad spur reached Nyack) the census still listed John W Felter as a ship carpenter, his son as a worker in a sail factory. James B. Voorhis, a 60-year-old ship carpenter, owned $8000 worth of real estate. Through a sheriff’s sale in August of the following year, Voorhis picked up the southern yard, so that for the first time in a century the entire boatyard now had a single owner. In 1872, a John W. Voorhis (age 39, his relationship to the owner of the yard unclear) is building 100 and 115-foot schooners in Upper Nyack, and the next year he launches a 300-ton three-master and a 400-ton schooner. In 1874, James B Voorhis and his wife, Rachel, sold the boatyard (for one dollar) to his son, James P Voorhis. The 1875 census reflects the changes towards industrialism in the Nyack area. Many of the inhabitants worked at the local shoe factories. In Upper Nyack, James B Voorhis, 64, listed himself as a carpenter. Up the street was 46-year old Robert Kennier, captain of a schooner; Kennier’s two sons were sailors. Also in the immediate neighborhood of the boatyard, Tunis Kent, 56, was a ferryboat pilot, and Moses Wyman and his son were both carpenters. So were John Perry and Oswith Perry. The estimated daily wage for a ship carpenter in 1875 was $3.25, compared to a shoemaker who got $2, or a blacksmith who got $3 a day. On July 20, 1875, the widow Eleanor Tallman sold James P Voorhis the underwater land by the boatyard for $100. Voorhis lived near the river on the southernmost part of his property. He also owned the store at the site of the present city hall (Castle Hts and Broadway). 1877 marked an economic collapse in Nyack; James B Voorhis retired from shipbuilding, age 67. Two years later, J.W(?) Voorhis was hurt at his Upper Nyack yard. There was apparently still a ferry landing at the yard because the Union Steamboat Company was paying taxes on $280,000 personal property in Upper Nyack but owned no real estate. In 1880, Moses Wyman, a ship’s carpenter and his son, Ebenezer, in the same trade, lived at what is now 12 Castle Hts. John Rose, a ship’s carpenter, lived at the corner of Perry Lane and Broadway with a brother who plied the same trade. The Perry family included John, 59, a ship carpenter, his brother Daniel, the same, and William, a sailor. John W Felter, at 14 Castle Hts was also a ship’s carpenter as was his 26 year-old son, Ino. Tunis Kent, on Ellen Street, was still a steamboat pilot and his neighbor, William Williams was a steamboat engineer. James Voorhis was 69 by now, and his two lots on river had declined in value and were worth a total of $7000. Peter Voorhis, 43, was also on the river building boats. A July 22, 1882 edition of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly included an etching of the “dome steamer” Meteor being built in Nyack. The double-chimneyed vessel is in the docks with Hook Mountain clearly visible in the background. In 1883, James P Voorhis was launching yachts at Upper Nyack. The community had turned more upper crust. The Schuller family donated money for the city hall and firehouse. In May of 1889, Voorhis was, according to the local paper, “talking about going to South America.” A divorce suit between Voris and his wife had her accusing him of striking and beating her and forcing her out of her bed at night, as well as using profane language; he denied everything, arguing: “[H]e would have been legally and morally justified in inflicting personal chastisement and moderate violence upon her in consequence of her language and manner of treatment of him ... that she has been in the habit of leaving defendant and young children and remaining away from one to fifteen consecutive days; that she had threatened to poison defendant, and that she had got into the habit of drinking beer and other stimulants to excess.” A month earlier, Voorhis had turned over the management of the yard to R.B. Rodenmond of Tompkins Cove. Rodenmond needed a yard that could handle bigger boats. An article at the time described the yard: “There are three marine railways on which to operate, besides the yards are better equipped for doing work than any place along the Hudson. In connection with this a large saw mill has also been purchased near the yards which has all the latest appliances for sawing out timber for vessels.” Rodenmond announced in May of 1889 that three vessels were being built, more coming; all men at work and more needed. As the local Evening Journal put it; “The present season at the Nyack shipyards is characterized by a remarkable degree of activity, and from present indications the coming Summer will bring a prosperity unequaled in many years past. “The Nyack boat-builders long ago acquired a reputation for first-class workmanship in their line, and one of the proudest facts which the Journal can announce is that this reputation is being splendidly maintained.” By 1890, the Upper Nyack population was 668. Moses and Charles Wyman were still ship carpenters and living at 12 Castle Heights, John Perry was also a ship’s carpenter along with John W Voorhis, but William Voorhis listed himself as a piano maker. Rodenmond rented the M.B. Demarest house on Castle Hts. By 1891, the James P Voorhis divorce case had ended in a hung jury and Mr. Voorhis was running a saloon in Harlem. In October of the next year, James B Voorhis (the father) died. He was nearly 82 years old and was described as having “built more sail vessels than any other builder along the river.” But since his time, the yard had run down considerably, and Rodenmond apparently couldn’t make a go of it despite prosperity in the “Roaring ‘90’s.” On May 18, 1893 Samuel Ayres bought the boatyard (hotel, dock and railroad) at public auction at the Hotel St. George. The yard employed 8 men; Ayres brought 15 more form his South Brooklyn boiler plant, which he had operated for the past 40 years. Ayres had purchased the yard because he’d recently acquired a farm in West Hempstead and wanted his work to be closer to home. In Brooklyn, Ayres had built boats for “Commodore Gerry, the Vanderbilts, and other prominent men in the city.” He set to work dredging the basin to 10’, adding a 400’ dock, as well as building a 100 x 50 foot three-story frame building. Two-thirds of this building still stands at the center of the present boatyard. Cost was estimated at $10,000 for the entire re-fitting. The operation would be called Ayres and Son. The “Son” was James C Ayres who, on October 16, 1899, bought the Youmans family house at 8 Castle Hts for $1600. By 1900, Upper Nyack’s population was 516, a decline. In 1905, John W Felter was still listed as a boat builder, age 72, Charles Wyman was a 56-year old boat builder, Andrew Kennier was a 47-year-old boat builder, James Ayres, 36, was a boat builder with his wife Alice. But James Ayres died that November 23 of apoplexy and a cerebral hemorrhage. The obituary listed him as having been 12 years in Upper Nyack, which means he lived in the area before his father bought the boatyard. The next dozen years, the yard remained in the possession of Alice Ayres who apparently kept it going, although it was once again on a decline. In May, 1917, she sold to International Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering to produce subchasers for WWI. Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, commissioned designs for an effective antisubmarine vessel, which could be quickly built in small boatyards by civilians already skilled in wooden boat building. The winning design was for an 110-foot long vessel, with 15-foot-6-inch beam and drawing 4-foot-6-inches. Each subchaser had three 220 horsepower engines and could go at 17 knots with a 1000-mile cruising range. The Government wanted 500 of these “swatters” built in the first year, or roughly one a week. In Nyack, the new owners of the yard planned to meet this demand by employing between 200 and 500 men with a $12,000 weekly payroll. The first subchaser was launched in the old boatyard on December 15, 1917. The paper reported that it made the 40-mile trip from Upper Nyack to the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 2 hours and 10 minutes.  Ten rescue boats in Hudson River, Upper Nyack, were built at the Julius Petersen Boatyard. This is written on the back: "Feb. 1945, Julius Petersen, Inc. Aircraft Rescue Boats; Given to Edward B. Leahey, MD, South Nyack in 1980 by Craig Carle, owner of Petersen Shipyard. 8/14/96 EBL MD." Nyack Library Local History Collection. AuthorDaniel Wolff is a journalist, an author of nonfiction books, a Grammy-nominated music writer, a filmmaker, a song lyricist, and a poet. If you enjoyed this history article, please consider a donation to support the RiverWise project:

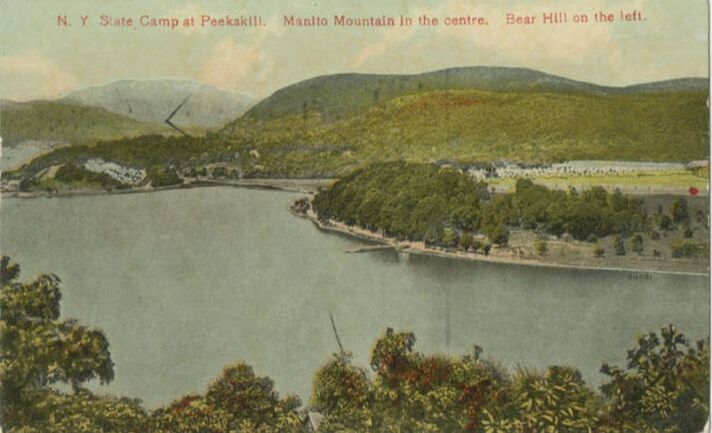

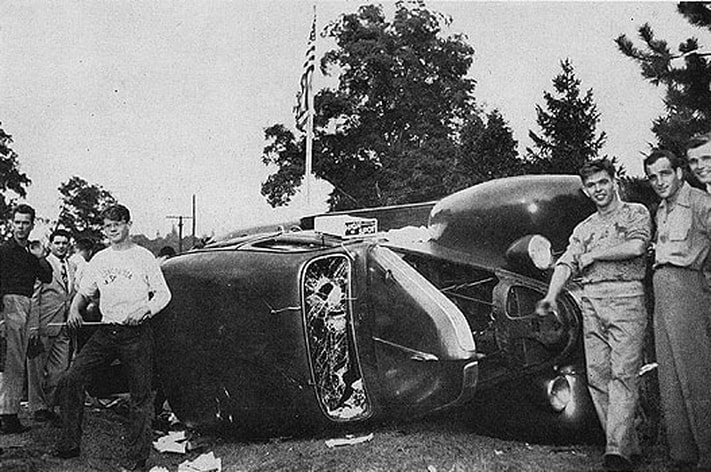

New York State Camp at Peekskill. Manito Mountain is in the center and Bear Hill is on the left. Looking down a hill over the Hudson River. Bear Mountain (formerly called Bear Hill) is one of the best-known peaks of New York's Hudson Highlands. Located mostly in Orange County's Town of Highlands, it lends its name to a nearby bridge and the state park that contains it. Courtesy New City Library. Peekskill is a city on the east shore of the Hudson River in Westchester County. In the early 17th century Dutch colonist Jan Peeck came to this area and met with the Lenape people near the confluence of the Annville and Peekskill Hollow Creeks. Jan Peeck lent his name to the creek which became known as "Peeck's Kill" (or the creek of Peeck). The town takes its name from the creek, even though the creek which flows down to the Hudson River is now known as the Annsville Creek. The Annsville Creek gave the town of Peekskill a important protected harbor. During the American Revolution, Peekskill hosted Fort Independence, which served as the headquarters for the Continental Army in 1776. As with many Hudson River port towns, Peekskill grew in the 19th century as industrialization gave rise to iron foundries and factories, including the Peekskill Chemical Works, which eventually became the company that would found Crayola Crayons. Peekskill is probably most famous, however, for the Peekskill Riots, which technically took place just north of Peekskill. In 1949 African American singer Paul Robeson was scheduled to perform at a benefit concert for the Civil Rights Congress. 1949 was a time of growing political unrest in the United States. Increasingly, people who argued against white supremacy and supported trade unions and civil rights were labeled "communists," including Pete Seeger. In particular, Robeson advocated for peace with the U.S.S.R., which angered many people. Robeson had performed at least three times before in Peekskill without incident, but earlier in 1949 he had been called before the House Committee on Un-American Activities to account for his travels to the U.S.S.R. He had appeared at the Soviet-sponsored Paris Peace Congress in April, 1949, where he gave a speech. The Associated Press ran a quote of Robeson's speech that turned out to be fabricated and inflamed existing tensions as it was published in newspapers around the country. Local Peekskill papers condemned the speech and Robeson's planned appearance in Peekskill. On the day of the planned concert on August 27, 1949, protesters attacked concert-goers and the violence left 18 people injured. The concert was postponed until September. On September 4, 1949, the concert went on as planned, but as the performers and concert-goers left, a gauntlet of protesters, including members of the VFW and American Legion, threw rocks at the departing vehicles. Pete and Toshi Seeger and their families shared a vehicle with Woody Guthrie, and Pete later used some of the rocks thrown through the windows to build the chimney of his house in Fishkill. In both instances of violence, the local police largely declined to intervene, despite injuries. The riots drew widespread condemnation among the general public, but the politics of defending people deemed communists were untenable at that time, and no government action was taken in response to the riots. Many government officials and the press denounced the violence as the fault of communist agitators. In the wake of the violence, Paul Robeson appearances in other cities were subsequently canceled, his name stricken from honorable records, and news footage of him destroyed. He was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee again in 1956, and he pled the Fifth Amendment, knowing that being a member of the Communist Party was legal in the United States. By then, anti-communist fervor in the United States that had been whipped up by Senator Joe McCarthy had begun to decline, and by the 1960s McCarthy was largely discredited. In 1999, on the 50th anniversary of the September 4 riots, the Paul Robeson Foundation held "A Remembrance and Reconciliation Ceremony" in Peekskill. Pete Seeger, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Paul Robeson, Jr., and local activists. To those who hear the word "Peekskill" today, most often what comes to mind is not the forays of Jan Peeck or iron forges, but the dramatic violence in a time of burgeoning social and political unrest. If you enjoyed this history article, please consider making a donation to support the RiverWise project.

Garrison is a hamlet located in Putnam County, NY just across from West Point. Named for Revolutionary War Lieutenant Isaac Garrison, who fought and was captured at the Battle of Fort Montgomery, Isaac Garrison operated a ferry between Garrison and West Point. Garrison is also near World's End, where the Hudson River is at its deepest - just over 200 feet deep. Famed by sailors it is also one of the areas of unpredictable winds on the Hudson and home to many accidents and shipwrecks. This area was all the more terrifying because the depth of the water meant recovery of a sunken vessel was nearly impossible. In the late 19th century, Garrison also became the site of a railroad accident. On the early morning of October 24, 1897, as most passengers were still asleep in their sleeper cars, the train derailed along the Hudson River. The embankment under the tracks gave way, dumping three sleeper cars into the Hudson River and killing 18 people by drowning. Investigators failed to find hard evidence of what had happened, most most speculated that the embankment had given way, causing the derailment. Others in the media speculated about explosives and sabotage. Just two weeks prior, a boulder in the middle of the tracks had caused another derailment. Garrison has one more claim to fame. For the 1969 film "Hello, Dolly!" historic downtown Garrison was used as a location shoot to portray 1890s Yonkers, NY. If you enjoyed this history article, please consider a donation to support the RiverWise project:

Newburgh’s Shipbuilding Heritage in the Days of Wooden Ships & Sail By William duBarry Thomas (originally published in the Pilot Log, 2000) Newburgh was the shipbuilding center of the mid-Hudson region for well over a century and a half. Although the earliest accomplishments of local shipwrights are clouded by the passage of time, sailing vessels were constructed during the colonial days by such men as George Gardner, Jason Rogers, Richard Hill and William Seymour along the village’s waterfront, which extended approximately from the foot of present day Washington Street north to South Street. Strategically well placed at the southernmost point before one entered the Hudson Highlands, Newburgh became the river transportation center, serving the inland towns and village to the north and west. The Highlands form a magnificent scenic delight in the mid-Hudson region, but in the pre-railroad era they were decidedly unfriendly to the movement of goods and people. In short, the Hudson became a marine highway which connected upstate regions to the Metropolis at its mouth. A significant freighting business therefore developed at Newburgh, and, in addition, the village became one of the region’s bases for the whaling industry. Both of these undertakings required sailing vessels, and with forests of suitable timber nearby, the local shipbuilders were well placed to support the burgeoning commerce on the river. Much of this changed with the introduction of the steamboat in the summer of 1807, when Robert Fulton’s North River Steamboat made her first trip to Albany. It was inevitable that steam should be adopted almost universally on America’s waterways. The earliest steamboat built at Newburgh is reputed to have been the side-wheel ferry Gold Hunter, constructed in 1836 for the ferry between Newburgh and Fishkill Landing. We are not certain of the identity of her builder, but her appearance coincided with the start of local shipbuilding by the dynasty which dominated that industry locally for 110 years – Thomas S. Marvel; his son of the same name; and his grandson, Harry A. Marvel. The shipbuilding activities of these three generations of the Marvel family encompassed the period from 1836 until 1946, when Harry Marvel retired from business. Although their activity was not continuous throughout this period, the reputations of these men as master shipbuilders survived the periodic and all too frequent ups and downs that have always plagued this industry. The senior Thomas Marvel, born in Newport, Rhode Island in 1808, served his apprenticeship as a shipwright with Isaac Webb, a well known shipbuilder in New York. Around 1836, he moved to Newburgh and commenced building small wooden sailing vessels, sloops, schooners and the occasional brig or half-brig, near the foot of Little Ann Street, later moving to the foot of Kemp Street (no longer in existence). Among the vessels he built was a Hudson River sloop launched in the spring of 1847 for Hiram Travis, of Peekskill. Travis elected to name his vessel Thomas S. Marvel, a name she carried at least until she was converted to a barge in 1890. An unidentified 160-foot steamboat was built at the Marvel yard in 1853. She was described by the local press as a “new and splendid propeller built for parties in New York.” Possibly the first steamboat built by Thomas Marvel, this vessel was important for another reason – she was propelled by a double-cylinder oscillating engine built on the Wolff, or high-and-low pressure principle. Ernest Wolff had patented his design in 1834, utilizing the multiple expansion of steam to improve the efficiency of the engine. The Wolff engine was a rudimentary forerunner of the compound engine, which did not appear for another two decades. The younger Thomas joined his father in 1847, at the age of 13. The young man, who was born in 1834 in New York, was entrusted with building a steamboat hull in 1854. This was a classic case of on-the-job training, for the boat was entirely young Tom’s responsibility. She is believed to have been Mohawk Chief, for service on the eastern end of the Erie Canal. The 85-3/95 ton Mohawk Chief, 86 feet in length, was described in her first enrollment document as a “square-sterned steam propeller, round tuck, no galleries and no figurehead.” The dry, archaic language of vessel documentation was hardly accurate, for her builder’s half model, still in existence, proves that she was a handsomely crafted little ship with a graceful bow and fine lines aft. The elder Thomas Marvel retired from shipbuilding at Newburgh sometime before 1860. He later built some additional vessels elsewhere, including the schooner Amos Briggs at Cornwall. He may have commanded sailing vessels on the river in his later years, for he was referred to from time to time as “Captain Marvel.” By the mid-1850s, the younger Thomas Marvel had become a thoroughly professional shipwright, and undertook the management of the yard’s operation, at first as the sole owner and later in partnership with George F. Riley, a local shipwright. The partnership continued until Marvel volunteered for service in the Union Army almost immediately after the start of the Civil War in April 1861. He served as Captain of Company A of the 56th Regiment until he was mustered out due to illness in August 1862. He returned to Newburgh, but shortly afterwards moved to Port Richmond, Staten Island, where he built sailing vessels and at least one steamboat. A two-year period in the late 1860s saw him constructing sailing craft on the Choptank River at Denton, Maryland, after which he returned to Port Richmond. During the Civil War and for a few years afterwards, George Riley continued a modest shipbuilding business at Newburgh, later with Adam Bulman as a partner. They went their separate ways in the late 1860s, and Bulman teamed with Joel W. Brown in 1871, doing business as Bulman & Brown. For the next eight years, they build ships in a yard south of the foot of Washington Street, where they turned out tugs, schooners and barges. Their output of tugs consisted of James Bigler, Manhattan, A.C. Cheney and George L. Garlick, and their most prominent sailing vessels were the schooners Peter C. Schultz (332 tons) and Henry Pl Havens (300 tons), both launched in 1874. Another source of business was the brick-making industry, which required deck barges to move its products to the New York market. Nearly all of the 19th century New York City was built of Hudson River brick, and the brick yards on both shores of Newburgh Bay contributed to this enormous undertaking. In 1872 alone, Bulman & Brown built at least five brick barges for various local manufacturers. Vessel repair went hand in hand with construction. Bulman & Brown built and operated what might have been the first floating dry dock at Newburgh. In 1879, the firm moved to Jersey City, New Jersey, and Newburgh lost a valuable asset. This prompted Homer Ramsdell, the local entrepreneurial steamboat owner, to finance the construction of a marine railway located at the foot of South William Street. Ramsdell, whose interests included the ferry to Fishkill landing and the Newburgh and New York Railroad, as well as his line of steamboats to New York, wanted to be sure that his fleet could be hauled out and repaired locally without the need for a trip to a New York repair yard. The mid-1870s, which marked the end of the wooden ship era at Newburgh and the start of the age of iron and steel, brings us to the close of this portion of the sketch of the area’s shipbuilding. From this time onward, the local scene would change radically. The firm of Ward, Stanton & Company, successors to Stanton & Mallery, a local manufacturer of machinery for sugar mills and other shoreside activities, entered shipbuilding and persuaded Thomas S. Marvel to join the company in 1877 to manage its shipyard. Newburgh, which had been incorporated as a city in 1865, was about the enter the major league in ship construction. Here is a full list of all the boats built by Marvel Shipyard over the years.

If you enjoyed this history article, please consider donating to support the RiverWise project.

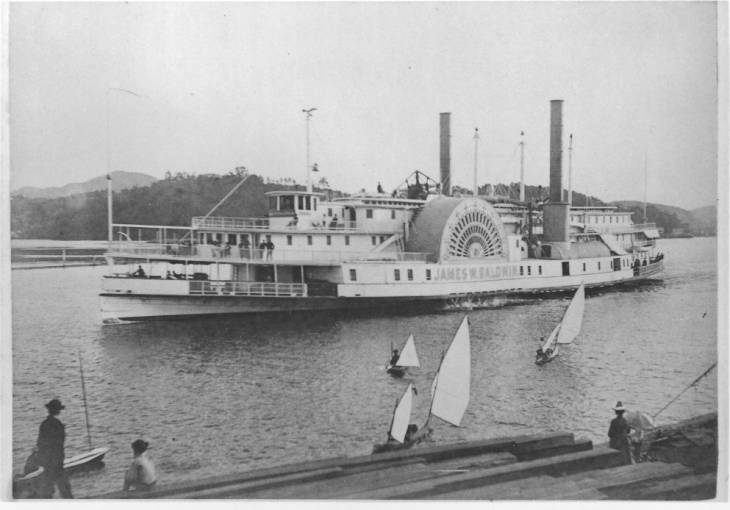

Captain Sam did a lovely video over the wreck of the sloop First Effort, which was cataloged in the 1908 book Sloops of the Hudson, and mentioned the reputation that the steamer James W. Baldwin had for collisions. Thankfully, we have in our collection the published articles of Captain William O. Benson, who just happens to recount that history! The article below is a verbatim transcription of his original article.

The ‘James W. Baldwin’ Becomes The ‘Central Hudson’

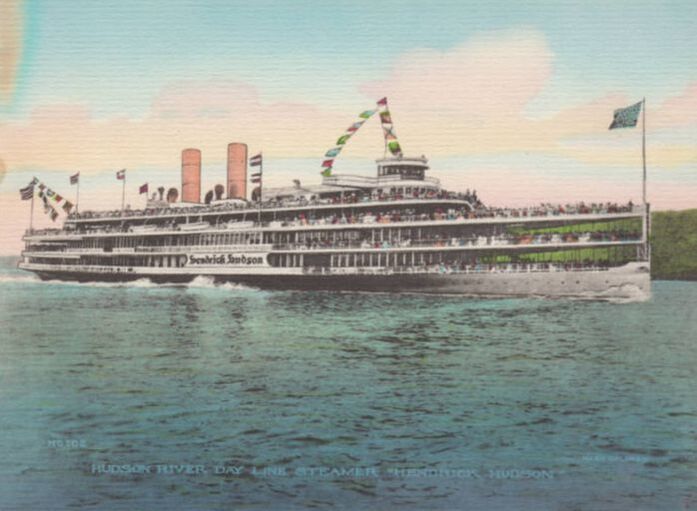

The Kingston Daily Freeman, Sun., Nov. 25, 1973 By CAPT. WM. O. BENSON The old Rondout to New York night boat “James W. Baldwin,” that linked Rondout and Kingston with the metropolis to the south longer than any other, had her share of mishaps. The ‘‘Baldwin” ran on the river during an era when sloops and schooners still plied the Hudson in great numbers. On one dark and hazy night, while making a landing at Marlborough, the steamer mistook a sloop’s lantern for a light on the dock. She hit the sloop, named “First Effort,” which sank in 50 feet of water and, which to this day, is still on the bottom of the river. Another time in 1904 on a black, rainy night off Esopus, the “Baldwin” collided with an ancient sloop named '‘Contrivance.” The sloop, carrying a load of brick, was 86-years-old and was sunk. The captain of the sloop, Calvin Delanoy, was drowned. On Wednesday, July 4, 1888, the “James W. Baldwin” was involved in an accident that subsequently led to the steamboat's name being changed to “Central Hudson.” On that holiday evening shortly after 8 p.m. on leaving her dock at Newburgh, a small steam launch carrying eight people crossed the steamboat's bow. Despite the steamer's frantic efforts to back down, it was too late to get the way off the “Baldwin.” The launch was hit amid-ships [sic] and immediately sank. Quick action by the “Baldwin's" crew saved six of the eight people in the launch. Of the two persons lost, one unfortunately happened to be Mrs. Benjamin B. Odell, Jr., whose husband would later become Governor of New York State and head of the steamboat company that years later was to acquire ownership of the “James W. Baldwin.” Of the accident itself, a coroner's jury later found the launch to be at fault and exonerated the men in the “Baldwin's” pilot house of blame. During the latter half of the 19th century, virtually every community of any size along the Hudson River was linked to New York by its own steamboat line. In 1899, the three independent steamboat companies serving Newburgh, Poughkeepsie and Kingston were consolidated into one company, the new company being named the Central Hudson Steamboat Company. One of the prime movers behind the consolidation and an officer of the new company was Benjamin B. Odell, Jr. of Newburgh, whose wife had been drowned in the “Baldwin” incident 11 years before. Since the “James W. Baldwin” was one of the two steamers of the Kingston line acquired in the merger, she came under the Odell ownership. In 1903, the “Baldwin” underwent a rebuilding which included new boilers and a dining room on the saloon deck forward. Allegedly as an aftermath of her tragic accident of July 4, 1888, the “James W. Baldwin” at this point was renamed “Central Hudson.” As a final irony, the Central Hudson Line built a new steamer in 1911 to replace the “James W. Baldwin,” now named “Central Hudson.” The new steamboat's name was “Benjamin B. Odell.” Back in the glory days of the “James W. Baldwin” on the Rondout run, the steamer, particularly on Saturdays, would have brushes with the “Mary Powell.“ Both steamboats were scheduled to arrive at Rondout on summer Saturday evenings at about the same time. Coming up off Esopus both boats would frequently be neck and neck with throttles wide open. The Chief Engineer of the “Baldwin“ would pace back and forth across the main deck commanding his firemen, “Don’t you dare let that steam pressure drop one ounce, or you can go ashore at Rondout for good!" Up in the pilot house of the “Baldwin,” the pilots would try and jockey for position and get on the west side of the channel so their steamer would be on the inside of the turn going around Esopus Meadows lighthouse. Sometimes the “Baldwin” would cut the Esopus lighthouse so short her port paddle wheel would stir up the mud. When they got off Sleightsburgh and if they had a good high tide, I understand they would sometimes cut inside the Rondout lighthouse —which at that time stood on the south side of the creek. Then, how the water would turn muddy! If they beat the “Powell” to Rondout Creek, the “Mary Powell” would have to lay out in the river and wait for the “Baldwin” to go in the creek and get turned around. At times like that, sometimes the crew of the “Baldwin” would take their sweet time turning and handling lines just to show the people waiting on the dock the “Baldwin” was on time landing, and the “Powell” would be late landing her passengers—sort of 19th century one upsmanship. As the first decade of the 20th century drew to a close, the career of the old “James W. Baldwin” also approached its end. During 1910, the Central Hudson Line contracted for a new steamboat, designed as a replacement for the “Baldwin.” The new steamer, the “Benjamin B. Odell” made her first trip into Rondout Creek on April 11, 1911, bringing to a close the 50 year service of the “Baldwin,” now named “Central Hudson”, on the Rondout run. In May of 1911, the “Central Hudson” was chartered by a company known as the Manhattan Line which had sprung up as an opposition line to the Hudson River Night Line running to Albany and Troy. The “Central Hudson“ was to run with the steamer “Kennebec,” an old Maine steamboat. On her trip down river on May 20, 1911 in heavy fog, the '‘Central Hudson” ran aground below Jones Point, opposite Peekskill. She was aground some 13 hours before getting off and continuing on to New York. On the very next trip up river, heavy with freight, the “Central Hudson“ grounded again, making the turn too quick before getting up to Gee’s Point at West Point. Unfortunately, she ran aground at high water. The Cornell tugboats “E. C. Baker” and "G. W. Decker” were sent down from Newburgh to try and pull her off. By the time they got there, however, the tide was ebbing and the captain of the “Decker” later told me the rods from her spars were getting slack in them, an indication she was hogging. The way her bow was aground, the tugboat captains thought if they pulled on her, at her age, and if she came off, the “Central Hudson” might sink in the deep water there before they could get her beached. The captain of the “Decker“ observed, “If they had had a Central Hudson Line crew on the old “Baldwin” like Amos Cooper and Abram Brooks, the accident would never have happened. Look at the hundreds of times those two men took her around there in years past without anything happening.” Finally, Merritt, Chapman and Scott, the marine salvagers, had to be hired to free the “Central Hudson.” After getting her afloat, it was found she was so badly strained, the old steamer would have to he retired. She was towed to Newburgh where she lay for nearly six months. On Nov. 15, 1911, the “Central Hudson,” or as she was better remembered as the “James W. Baldwin” was towed to the old steamboat graveyard at Port Amboy, N.J. and broken up. During her long career, the steamboat was commanded by a long line of well known Hudson River captains. The list included Captains Jacob H. Tremper, Jacob H. Tremper, Jr., Reuben H. Decker, Weston L. Dennis, Arthur Palmer, Zack Rossa and F. L. Simpson. For decades after she was gone, the old “James W. Baldwin” was remembered by steamboatmen and spoken of kindly—as the old side wheeler that after running between Kingston and New York for 50 years did not want to go off on a new route with a new crew.

If you enjoyed this history article, please consider donating to support the RiverWise project.

In the 18th century, Poughkeepsie was a main port on the Hudson River and was involved in shipbuilding. During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress ordered two sea-going frigates to be built at Poughkeepsie as part of legislation to build 13 frigates throughout the colonies. Three-masted frigates were the backbone of many navies although smaller than more heavily gunned ships of the line. The Act of December 13, 1775 authorized (3) 24 gun frigates, (5) 28 gun frigates and (5) 32 gun frigates in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire and Connecticut. Politics were an important factor in distributing these contracts among the former colonies. The Poughkeepsie frigates Congress (28 guns) and Montgomery (24 guns) were begun in 1776 by Lancaster Burling and launched unfinished into the Hudson in October of the same year. There was no urgency to complete them given the British control of New York City and blocked access to the sea. Men and materiel were diverted to more strategic locations including Lake Champlain. The fitting out of the two frigates apparently languished. The frigates are believed to have been approximately 120 ft and 126 ft in length and 32 ft to 34 ft in beam. Based on surviving plans for a similar 28 gun frigate, the Congress featured a largely open gun deck with raised quarterdeck and forecastle. She was to have been armed with (26) 12 pounders and (2) 6 pounders. The Montgomery, named for the fallen general Richard Montgomery who died in the assault on Quebec in 1775, was to have been armed with (24) 9 pounders. Slightly shorter, her basic configuration was likely similar to that of the Congress. During the British advance on forts Montgomery and Clinton in 1777, the two unfinished frigates were rushed down the Hudson to support the American defenses. They likely carried partial rigs and may not have carried their full complement of guns. The forts were attacked from the rear and both fell. Unable to retreat back up the river due to tide and wind, the Americans burned the ships and escaped in small boats in order to prevent the capture of the valuable frigates. To date, no evidence of either ship has been found in the river bottom leading to some speculation that they may not have sunk and that their salvage went unnoticed after the battle. No images of either frigate survives, likely becacuse they remained unfinished. But other frigates, including the USS Confederacy, pictured here in a painting by William Nowland Van Powell, were completed, though the Confederacy also did not survive the Revolution. In fact, almost all of the frigates of the Continental Navy did not survive, either due to damage in battle, capture, or because they were sunk to avoid capture, like the Congress and Montgomery. you enjoyed this history article, please consider donating to support the RiverWise project.

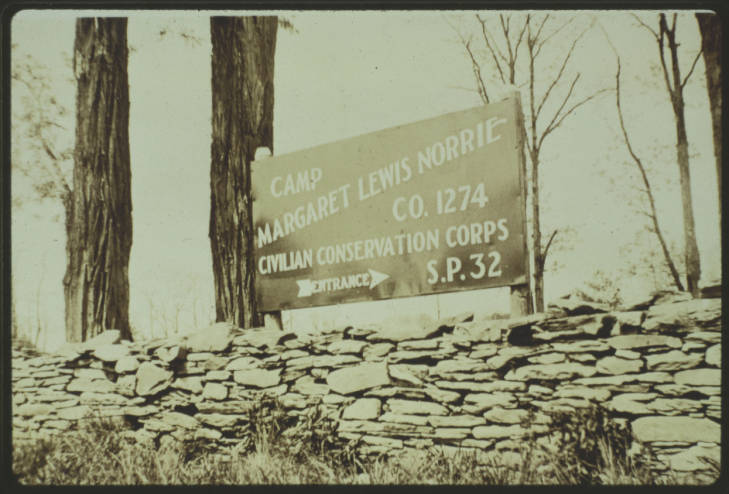

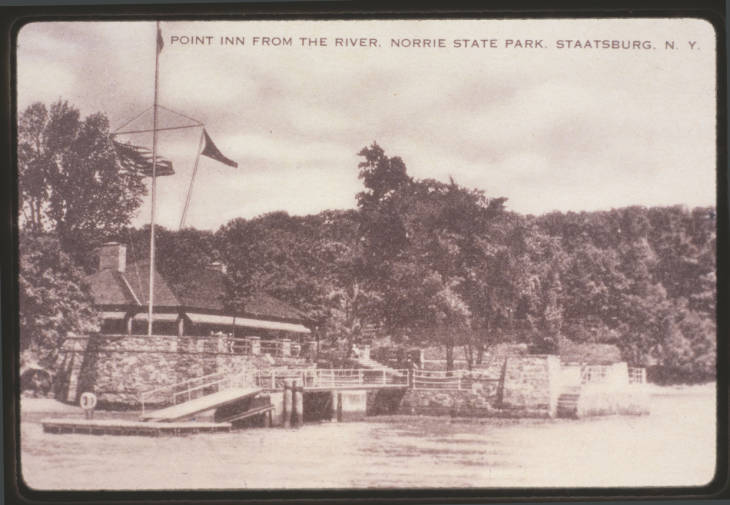

Norrie Point is a small point on the east shore of the Hudson River. The point and 323 acres of surrounding park lands were donated to New York State in 1934. Between 1934 and 1937, the height of the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) turned the donation into a public park. Over 200 men were encamped at the park and built roads, park facilities, and the "Point Inn." Completed in the spring of 1937, the Point Inn was built by the CCC right on the tip of Norrie Point. Work on the Inn was done throughout the cold winter months. It was one of their last projects before the camp was closed in 1937. The Point Inn opened as a privately operated restaurant starting on July 1, 1937. The Point Inn remained a popular restaurant spot until the mid-1960s. In 1954 the Norrie Boat Basin opened to the public, bringing more tourists and recreation to Norrie Point. In 1938 the Ogden Mills family donated an additional 190 acres and their family mansion, built in 1894. Multiple other land acquisitions throughout the 1960s and ‘70s and a more recent one in 2003 have dramatically expanded the public lands to over 1,000 acres shared between two state parks commonly referred to as Mills/Norrie. In the 1980s, the Point Inn was converted into the Norrie Point Environmental Center. Today the center is home to the Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve. In 1982, four distinct tidal wetland sites on the Hudson River Estuary were designated the Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve as field laboratories for estuarine research, stewardship and education. Stockport Flats in Columbia County, Tivoli Bays in Dutchess County, and Piermont Marsh and Iona Island in Rockland County all fall within the Reserve. The Reserve is operated as a partnership between the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and relates to federally-designated and state-protected sites along 100 miles of the Estuary. Staff and researchers at the Norrie Point Educational Center help protect some of the Hudson River's most important and biodiverse wetlands and provide public environmental education. To learn more about the Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve, visit their website. If you enjoyed this blog post about the history of Norrie Point, please consider donating to support the RiverWise project.

The Port of Rondout, as the Kingston waterfront was once known, was a bustling place for much of the 19th century. That was due in large part to the Delaware & Hudson Canal, which connected to Pennsylvania coal country in Honesdale, PA and terminated at Rondout, with the last (or rather, the first) lock at Eddyville.

The D&H Canal officially opened in 1828, but the Rondout to Port Jervis section opened in 1827. With the increased canal traffic and influx of anthracite coal, Rondout boomed. The easy availability of coal also meant that there was a ready source of inexpensive fuel for steamboats. So while the early days of cargo transportation coming out of the Port of Rondout was primarily by sail freight, steam freight soon began. In the 1830s, Thomas Cornell came with a sailing sloop to Rondout to ship coal from the D&H Canal. A native of White Plains, N.Y. Cornell was just twenty-two years old. Until then, sailboats had done the work of carrying freight and passengers, but Cornell saw that steam-powered vessels were the future. In a few years, he became the owner and operator of steamboats running between Rondout and New York. Cornell settled in Rondout, where he established the Cornell Steamboat Company. In those booming years of growth and construction, there was plenty of business for steamboats plying the Hudson. New York City’s thriving metropolitan area needed coal from the D&H Canal, ice that was harvested in winter from the frozen river, building material produced in the mid-Hudson valley, brick, lumber, stone, and cement – and agricultural products grain, livestock, dairy, fruit, and hay – which came from near and far. Rondout Creek offered the best deep-water port in the Hudson Valley, and thus became the center of maritime activity between New York and Albany. The Cornell Steamboat Company made its headquarters in Rondout village, where many boats were berthed and repaired, and some were built. Between 1830 and 1900, few harbors of comparable size anywhere in America were as busy as Rondout Creek. By the mid-1800s, the Hudson River had many sidewheel steamboats passing north and south, one grander than the other. They carried both freight and passengers, and speed was of the essence – both for bragging rights and because passengers favored the fastest boats. In the 1860s, Thomas Cornell acquired Mary Powell, the Hudson River’s fastest and most beautiful passenger boat. In this time, Cornell built a magnificent sidewheeler to ply the route from Rondout to New York. She was named in his honor – Thomas Cornell - and was one of the finest vessels operating on the Hudson. Steamboats not able to compete in speed or luxury often were turned into towboats, hauling loaded barges that were lashed together to be towed up or down the river. Cornell began to develop a fleet of towboats, which in time would be replaced by tugboats, designed and built especially for towing on the river. After the Civil War, Cornell was joined in the business by Samuel D. Coykendall, who became his son-in-law as well as a partner in the firm. The combination of Thomas Cornell and S.D. Coykendall soon would create the most powerful towing operation on the Hudson River. At its peak in the late 1800s, the Cornell Steamboat Company ran more than sixty towing vessels and was the largest maritime organization of its kind in the nation. Early in 1890, after contracting pneumonia, Thomas Cornell died at home at the age of 77. In son-in-law S.D. Coykendall, Cornell had a worthy successor. During a career of more than fifty years, Thomas Cornell built a mighty business empire and became a leading figure in New York and the nation. In addition to running the Cornell Steamboat Company and the Kingston-Rhinecliff ferry, he built and operated railroads on both sides of the Hudson, helped establish two banks, was a principal in a large Catskill Mountain hotel, and served two terms in Congress. By 1900, the Cornell Steamboat Company had given up the passenger business and turned completely to towing. There were more than sixty steam-powered towing vessels and tugboats in the Cornell fleet. Their boilers were fired by burning coal. Cornell vessels were well-known on the river, with their familiar black and yellow smokestacks clearly recognizable from the northern canals to New York harbor. As the years passed, S.D. Coykendall gave his six sons positions of authority and management in the Cornell business empire. “S.D.”, as he was known, was the leading citizen of Ulster County, heading up banks, developing railroads, operating a hotel and a ferryboat line, and building and operating trolley lines and an amusement park. He invested in many enterprises, including cement works, the ice industry, brickyards, and quarrying operations. In January 1913, S.D. Coykendall died suddenly at this home in Kingston at the age of seventy-six. Frederick Coykendall, who was forty years of age, succeeded his father as president of the Cornell Steamboat Company. Frederick lived in New York and was active in alumni and trustee affairs at Columbia University. He would become chairman of the university’s board of trustees and president of the university press. Assisting Frederick Coykendall was company vice president C.W. “Bill” Spangenberger, who had risen through the ranks since joining Cornell in 1933. When Frederick passed away in 1954, Spangenberger became president. Although company executives worked hard and with considerable success to rebuild Cornell, they were forced to sell out in 1958 when their largest customer, New York Trap Rock Corporation – a producer of crushed stone – offered to buy the company. Trap Rock retained Spangenberger as president of Cornell. In 1960, the Cornell Steamboat Company built Rockland County, an innovative, push-type towboat – the first of its kind in permanent service on the Hudson River. With Rockland County, a new age of towing began on the Hudson, but there would be no future for Cornell. Trap Rock soon acquired by a larger corporation, and the towing company was no longer needed. In 1964, the Cornell Steamboat Company finally closed its doors, after making Hudson River maritime history for an unprecedented one hundred and thirty-seven years.” [Editor's note: Portions of this article were originally published in the 2001 issue of the Pilot Log, the journal of the Hudson River Maritime Museum.] “RiverWise” Voyage Departs Thursday, August 13, 2020

Maritime Museum’s Educational Voyage Makes Stops From Kingston To NYC FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Kingston, NY – Are you RiverWise? Carbon-neutral vessels Solaris, of the Hudson River Maritime Museum, and Schooner Apollonia depart the museum’s Kingston, NY docks around 11:00 a.m. on Thursday, August 13, 2020 for the RiverWise: South Hudson Voyage. Over the next nine days they will travel to New York City, making stops in Hudson Valley communities each night. The two vessels will spend two days exploring New York Harbor, before returning up the Hudson River to Kingston. The schedule is as follows:

On the evening of Thursday, August 20, 2020, Solaris and Apollonia will be joined by several vessels from Classic Harbor Line for a fleet sail to the Statue of Liberty and Battery Park. Vessels are expected to arrive at the Statue of Liberty around 6:30 PM and Battery Park by 7:30 PM. Visitors are encouraged to view the vessels from shore or purchase tickets for the trip aboard Classic Harbor Lines vessels. For ticket information, please visit www.sail-nyc.com. Spectators are encouraged to view the vessels from shore at a variety of public park locations throughout the Hudson Valley. These parks are highlighted on the Hudson River Maritime Museum’s interactive map of the Hudson River, which includes historical information and photos of a variety of landmarks, including lighthouses, shipwrecks, historic sites, and more. The interactive map will also be updated throughout the day with times and locations of the vessels for the duration of the trip. All public programs will be done virtually. When the vessels are in port, no shore programs will be provided and visitors will please refrain from gathering in groups and practice social distancing at ports and parks to prevent the spread of coronavirus. Daily updates of the voyage, including live video, blog posts, and links, will be posted on the Hudson River Maritime Museum’s Facebook page – www.facebook.com/hudsonrivermaritimemuseum. The public is invited to like the museum’s page to be notified of updates. Daily updates will also be posted at the end of the day, along with additional history articles, on the RiverWise website’s Captains’ Log at www.hudsonriverwise.org/log. The South Hudson Voyage is part of a broader effort the museum calls “RiverWise.” During the voyage museum staff and crew will collect film footage, conduct interviews, and produce short films, photos, and social media content to teach the general public about the Hudson River and allow them to experience it in real-time, as the crew does, from the comfort of their own homes. After the voyage, museum staff will process the hundreds of hours of film footage collected on both voyages and begin to create short documentary films about the Hudson River and its history, with emphasis on the four themes highlighted this year – lighthouses, shipbuilding, towing, and sail freight. The museum is seeking donations to support both the voyage and the documentary films. The South Hudson Voyage is funded by individual donations and sponsorships. Mid-Hudson Federal Credit Union has sponsored in part Solaris, Apollonia, and the documentary films on Hudson River shipbuilding. The Daley Family Foundation has sponsored Apollonia. General support comes from the many individuals who have donated to the by-the-mile voyage campaign through PledgeIt. The North Hudson Voyage was sponsored in part by the Phelan Family Foundation, Ann Loeding, David Eaton, and the many individuals who donated to the PledgeIt campaign. Additional funding for both campaigns has been provided by the Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area. The museum is still seeking sponsorships to help cover the costs of the South Hudson Voyage as well as this year’s four documentary film themes – lighthouses, tugboats and towing, shipbuilding, and sail freight. If you would like to support the South Hudson Voyage and the museum’s documentary films, please visit www.hudsonriverwise.org/support for more information on sponsorship and donation opportunities. ### About the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Located along the historic Rondout Creek in downtown Kingston, N.Y., the Hudson River Maritime Museum is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization dedicated to the preservation and interpretation of the maritime history of the Hudson River, its tributaries, and related industries. HRMM opened the Wooden Boat School in 2016 and the Sailing & Rowing School in 2017. In 2019 the museum launched the 100% solar-powered tour boat Solaris. www.hrmm.org About Solaris. Solaris was built by the Hudson River Maritime Museum’s restoration crew under the direction of Jim Kricker. Solaris is the only US Coast Guard-approved 100% solar-powered passenger vessel in the United States. It does not plug in. Designed by marine architect Dave Gerr from a concept developed by David Borton, owner of Sustainable Energy, Solaris is commercial in design, meeting all U.S. Coast Guard regulations for commercial passenger-carrying vessels. www.hrmm.org/meet-solaris About the Schooner Apollonia. The Apollonia is the Hudson Valley’s largest carbon-neutral merchant vessel. Powered by the wind and used vegetable oil, Apollonia can transport her cargo sustainably. This mission-driven, for-profit business has a transparent and reproducible business model - to provide carbon-neutral transportation for shelf-stable local foods and products. Connecting the traditions of slow food, fair trade, and carbon neutrality, we will inspire and train a new generation of Hudson River stewards and create green living-wage jobs in the growing river-based economy. www.schoonerapollonia.com |

AuthorThis Captains' Log is kept by the captains and crew of Solaris and Apollonia and staff of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed