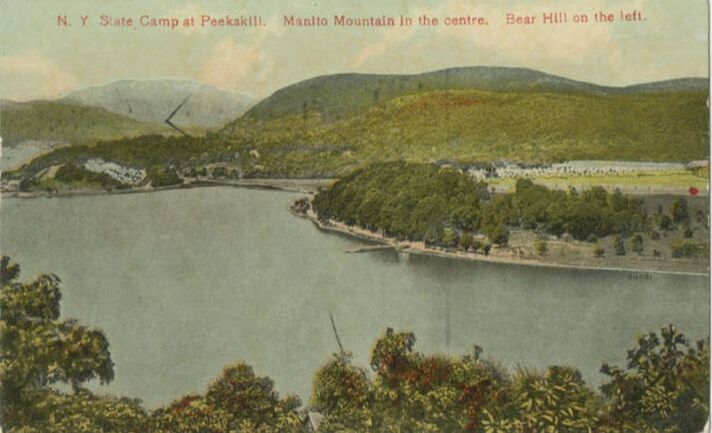

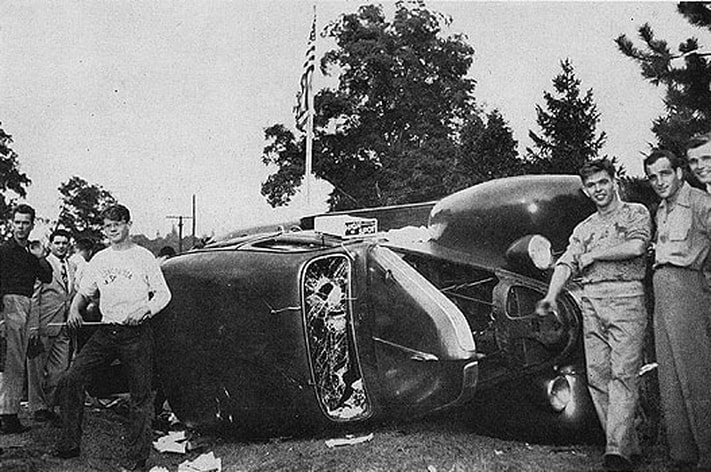

New York State Camp at Peekskill. Manito Mountain is in the center and Bear Hill is on the left. Looking down a hill over the Hudson River. Bear Mountain (formerly called Bear Hill) is one of the best-known peaks of New York's Hudson Highlands. Located mostly in Orange County's Town of Highlands, it lends its name to a nearby bridge and the state park that contains it. Courtesy New City Library. Peekskill is a city on the east shore of the Hudson River in Westchester County. In the early 17th century Dutch colonist Jan Peeck came to this area and met with the Lenape people near the confluence of the Annville and Peekskill Hollow Creeks. Jan Peeck lent his name to the creek which became known as "Peeck's Kill" (or the creek of Peeck). The town takes its name from the creek, even though the creek which flows down to the Hudson River is now known as the Annsville Creek. The Annsville Creek gave the town of Peekskill a important protected harbor. During the American Revolution, Peekskill hosted Fort Independence, which served as the headquarters for the Continental Army in 1776. As with many Hudson River port towns, Peekskill grew in the 19th century as industrialization gave rise to iron foundries and factories, including the Peekskill Chemical Works, which eventually became the company that would found Crayola Crayons. Peekskill is probably most famous, however, for the Peekskill Riots, which technically took place just north of Peekskill. In 1949 African American singer Paul Robeson was scheduled to perform at a benefit concert for the Civil Rights Congress. 1949 was a time of growing political unrest in the United States. Increasingly, people who argued against white supremacy and supported trade unions and civil rights were labeled "communists," including Pete Seeger. In particular, Robeson advocated for peace with the U.S.S.R., which angered many people. Robeson had performed at least three times before in Peekskill without incident, but earlier in 1949 he had been called before the House Committee on Un-American Activities to account for his travels to the U.S.S.R. He had appeared at the Soviet-sponsored Paris Peace Congress in April, 1949, where he gave a speech. The Associated Press ran a quote of Robeson's speech that turned out to be fabricated and inflamed existing tensions as it was published in newspapers around the country. Local Peekskill papers condemned the speech and Robeson's planned appearance in Peekskill. On the day of the planned concert on August 27, 1949, protesters attacked concert-goers and the violence left 18 people injured. The concert was postponed until September. On September 4, 1949, the concert went on as planned, but as the performers and concert-goers left, a gauntlet of protesters, including members of the VFW and American Legion, threw rocks at the departing vehicles. Pete and Toshi Seeger and their families shared a vehicle with Woody Guthrie, and Pete later used some of the rocks thrown through the windows to build the chimney of his house in Fishkill. In both instances of violence, the local police largely declined to intervene, despite injuries. The riots drew widespread condemnation among the general public, but the politics of defending people deemed communists were untenable at that time, and no government action was taken in response to the riots. Many government officials and the press denounced the violence as the fault of communist agitators. In the wake of the violence, Paul Robeson appearances in other cities were subsequently canceled, his name stricken from honorable records, and news footage of him destroyed. He was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee again in 1956, and he pled the Fifth Amendment, knowing that being a member of the Communist Party was legal in the United States. By then, anti-communist fervor in the United States that had been whipped up by Senator Joe McCarthy had begun to decline, and by the 1960s McCarthy was largely discredited. In 1999, on the 50th anniversary of the September 4 riots, the Paul Robeson Foundation held "A Remembrance and Reconciliation Ceremony" in Peekskill. Pete Seeger, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Paul Robeson, Jr., and local activists. To those who hear the word "Peekskill" today, most often what comes to mind is not the forays of Jan Peeck or iron forges, but the dramatic violence in a time of burgeoning social and political unrest. If you enjoyed this history article, please consider making a donation to support the RiverWise project.

1 Comment

Garrison is a hamlet located in Putnam County, NY just across from West Point. Named for Revolutionary War Lieutenant Isaac Garrison, who fought and was captured at the Battle of Fort Montgomery, Isaac Garrison operated a ferry between Garrison and West Point. Garrison is also near World's End, where the Hudson River is at its deepest - just over 200 feet deep. Famed by sailors it is also one of the areas of unpredictable winds on the Hudson and home to many accidents and shipwrecks. This area was all the more terrifying because the depth of the water meant recovery of a sunken vessel was nearly impossible. In the late 19th century, Garrison also became the site of a railroad accident. On the early morning of October 24, 1897, as most passengers were still asleep in their sleeper cars, the train derailed along the Hudson River. The embankment under the tracks gave way, dumping three sleeper cars into the Hudson River and killing 18 people by drowning. Investigators failed to find hard evidence of what had happened, most most speculated that the embankment had given way, causing the derailment. Others in the media speculated about explosives and sabotage. Just two weeks prior, a boulder in the middle of the tracks had caused another derailment. Garrison has one more claim to fame. For the 1969 film "Hello, Dolly!" historic downtown Garrison was used as a location shoot to portray 1890s Yonkers, NY. If you enjoyed this history article, please consider a donation to support the RiverWise project:

In the 18th century, Poughkeepsie was a main port on the Hudson River and was involved in shipbuilding. During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress ordered two sea-going frigates to be built at Poughkeepsie as part of legislation to build 13 frigates throughout the colonies. Three-masted frigates were the backbone of many navies although smaller than more heavily gunned ships of the line. The Act of December 13, 1775 authorized (3) 24 gun frigates, (5) 28 gun frigates and (5) 32 gun frigates in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire and Connecticut. Politics were an important factor in distributing these contracts among the former colonies. The Poughkeepsie frigates Congress (28 guns) and Montgomery (24 guns) were begun in 1776 by Lancaster Burling and launched unfinished into the Hudson in October of the same year. There was no urgency to complete them given the British control of New York City and blocked access to the sea. Men and materiel were diverted to more strategic locations including Lake Champlain. The fitting out of the two frigates apparently languished. The frigates are believed to have been approximately 120 ft and 126 ft in length and 32 ft to 34 ft in beam. Based on surviving plans for a similar 28 gun frigate, the Congress featured a largely open gun deck with raised quarterdeck and forecastle. She was to have been armed with (26) 12 pounders and (2) 6 pounders. The Montgomery, named for the fallen general Richard Montgomery who died in the assault on Quebec in 1775, was to have been armed with (24) 9 pounders. Slightly shorter, her basic configuration was likely similar to that of the Congress. During the British advance on forts Montgomery and Clinton in 1777, the two unfinished frigates were rushed down the Hudson to support the American defenses. They likely carried partial rigs and may not have carried their full complement of guns. The forts were attacked from the rear and both fell. Unable to retreat back up the river due to tide and wind, the Americans burned the ships and escaped in small boats in order to prevent the capture of the valuable frigates. To date, no evidence of either ship has been found in the river bottom leading to some speculation that they may not have sunk and that their salvage went unnoticed after the battle. No images of either frigate survives, likely becacuse they remained unfinished. But other frigates, including the USS Confederacy, pictured here in a painting by William Nowland Van Powell, were completed, though the Confederacy also did not survive the Revolution. In fact, almost all of the frigates of the Continental Navy did not survive, either due to damage in battle, capture, or because they were sunk to avoid capture, like the Congress and Montgomery. you enjoyed this history article, please consider donating to support the RiverWise project.

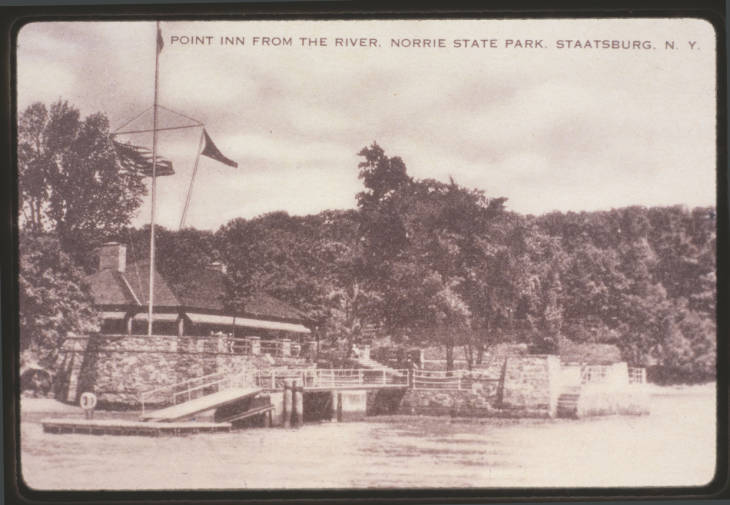

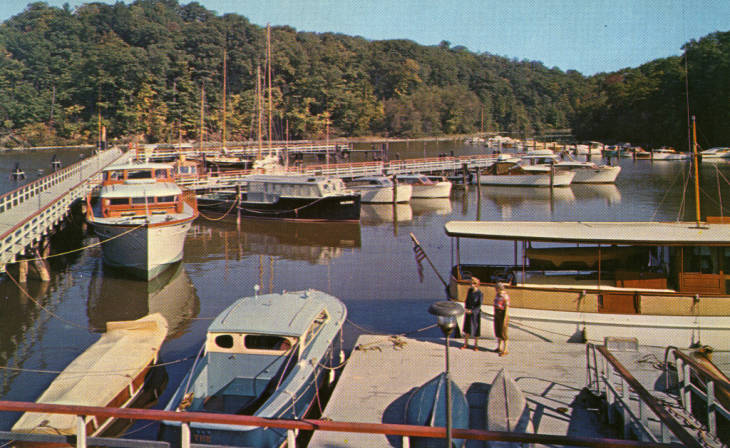

Norrie Point is a small point on the east shore of the Hudson River. The point and 323 acres of surrounding park lands were donated to New York State in 1934. Between 1934 and 1937, the height of the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) turned the donation into a public park. Over 200 men were encamped at the park and built roads, park facilities, and the "Point Inn." Completed in the spring of 1937, the Point Inn was built by the CCC right on the tip of Norrie Point. Work on the Inn was done throughout the cold winter months. It was one of their last projects before the camp was closed in 1937. The Point Inn opened as a privately operated restaurant starting on July 1, 1937. The Point Inn remained a popular restaurant spot until the mid-1960s. In 1954 the Norrie Boat Basin opened to the public, bringing more tourists and recreation to Norrie Point. In 1938 the Ogden Mills family donated an additional 190 acres and their family mansion, built in 1894. Multiple other land acquisitions throughout the 1960s and ‘70s and a more recent one in 2003 have dramatically expanded the public lands to over 1,000 acres shared between two state parks commonly referred to as Mills/Norrie. In the 1980s, the Point Inn was converted into the Norrie Point Environmental Center. Today the center is home to the Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve. In 1982, four distinct tidal wetland sites on the Hudson River Estuary were designated the Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve as field laboratories for estuarine research, stewardship and education. Stockport Flats in Columbia County, Tivoli Bays in Dutchess County, and Piermont Marsh and Iona Island in Rockland County all fall within the Reserve. The Reserve is operated as a partnership between the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and relates to federally-designated and state-protected sites along 100 miles of the Estuary. Staff and researchers at the Norrie Point Educational Center help protect some of the Hudson River's most important and biodiverse wetlands and provide public environmental education. To learn more about the Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve, visit their website. If you enjoyed this blog post about the history of Norrie Point, please consider donating to support the RiverWise project.

Acquired from the Esopus (a northern tribe of the Lenape/Delaware nation) by Barent Cornelis Volge in the 1650s, he operated a sawmill there, supplying lumber for the Rensselaerwyck. Between 1659 and 1663 the region was rocked by a series of violent incidents between the Dutch colonists and Esopus Lenape known as "The Esopus Wars." In 1664, the Dutch surrendered their colonial claim on the region to the English, and New Netherland became New York.

In the 1710s German Palatines settled in the area north of Saugerties known as West Camp (East Camp was across the Hudson) to produce pine pitch and tar for the British Navy. The endeavor largely failed, and most of the Palatines moved on. The region continued to be exploited for lumber and a number of saw mills were established over the 18th century. The hamlet of Saugerties was officially established in 1811, though it did not get the name Saugerties until 1855. Throughout the 19th century Saugerties became an industrial hub, with an iron works established in the 1820s and a series of paper mills in the 1830s. Bluestone quarrying and shipment, brick making, and ice harvesting were other major industries in the area. Although the village had passenger steamboat service as early as the 1830s, it wasn't until the 1880s that the Saugerties and New York Steamboat Company was established in the village, providing homegrown steamboat access. Many of the paper mills, especially the Martin Cantine Paper Company (1870s-1970s) continued in operation until the mid-20th century, when industrial manufacturing declined throughout the Hudson Valley. Saugerties is also the location of the Saugerties Lighthouse. First built in 1835 to mark the entrance to the Esopus Creek, the lighthouse was replaced in 1869 with the current structure, which still stands.

We stopped at the lighthouse yesterday to record some interviews, so stay tuned for a new video on the Saugerties Lighthouse coming soon! In the meantime, you can check out this documentary film from the Saugerties Lighthouse Conservancy.

See you this afternoon in Kingston!

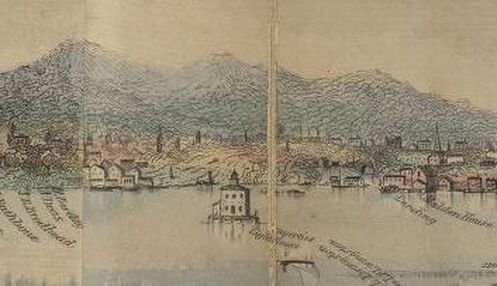

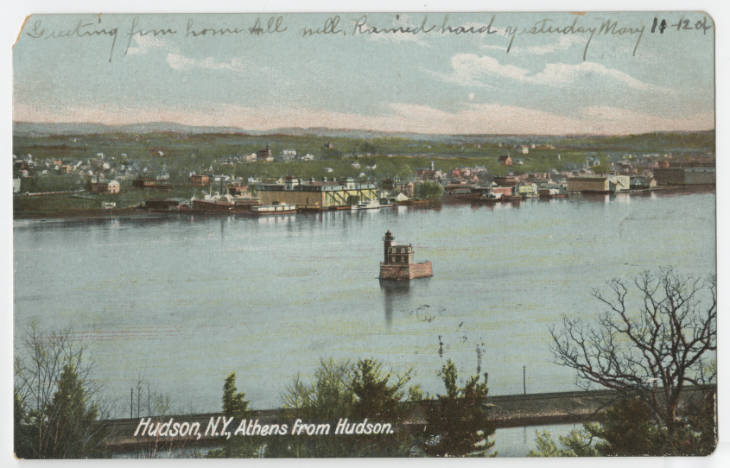

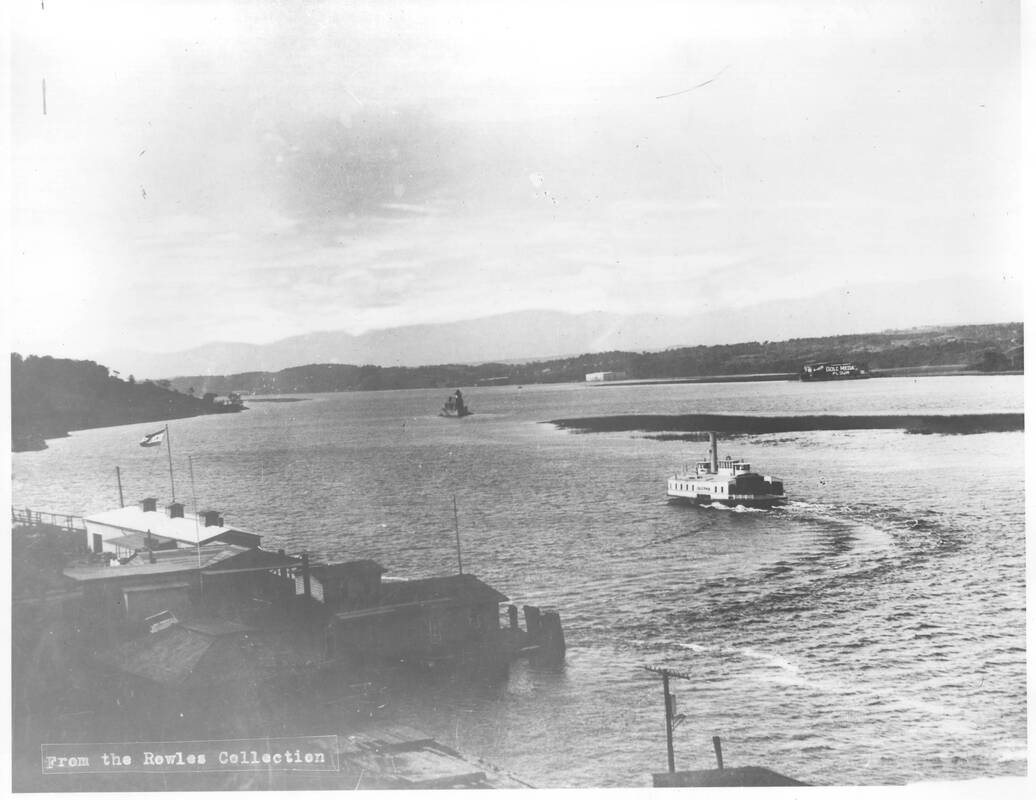

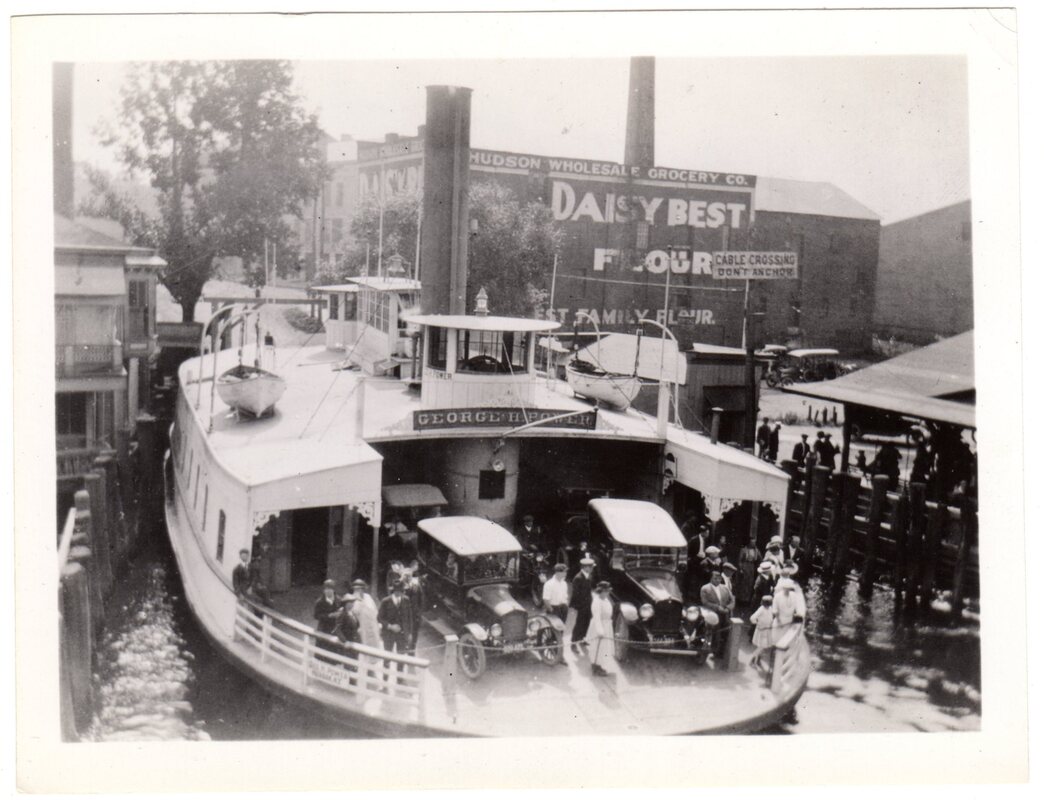

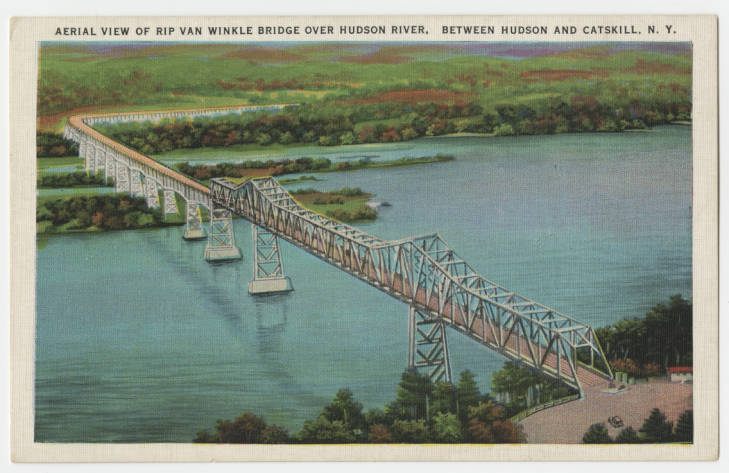

We spent the night at Athens, and as we get underway for our second-to-last day of the North River Voyage, we thought we would talk a little bit about the history of this river town, her sister city across the river, and the middle ground in between. AthensThe village of Athens is located on the west bank of the Hudson at the mouth of Murderer's Creek. Settled as early as the mid-1600s by Dutch colonists on Mohican land, Athens was originally called "Lunenberg" and the name "Murderer's Creek" may be a corruption of the Dutch words for mother or muddy. But the discovery of the body of a young woman on its banks in 1813 cemented its name in local lore. In 1815, Athens applied for incorporation with the state under its new name, inspired by the famous ancient city in Greece. Throughout the 19th century, it was home to shipbuilding, brickyards, and ice harvesting. Sometimes overshadowed by its larger sister city to the east, Athens has maintained much of its historic character, including the preservation of two Dutch colonial houses - the Albertus Van Loon House and Jan Van Loon House. HudsonAlso a colonial Dutch settlement founded on Mohican land, Hudson was once known as Claverack Landing. When New Netherland became New York, Quaker whalers from New England moved to Hudson to escape the privations of coastal pirates. Processing whale oil and ambergris out at sea, the ocean-going whaling ships sailed up to Hudson with their cargoes. Whale oil was a huge business in the 18th and early 19th century and many early lighthouses were lit by whale-oil lamps. But by 1819 the last whaling ship had sailed out of Hudson. The Hudson River Railroad was constructed in 1850, essentially cutting many east shore Hudson River port cities off from the river. In Hudson, the railroad tracks cut off the two bays that had once held so many sailing ships. Only small fishing and recreational vessels were able to leave the harbors .Access to docks and wharfs continued over grade crossings and eventually bridges. But Hudson was transitioning to an industrial manufacturing town. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, Hudson was an industrial port city, with iron works and foundries, brickyards, cement factories, and more. Hudson was chartered as a city in 1785 and thrived until the 1970s, when like many industrial Hudson River towns it suffered economic decline. As with Athens, Hudson has retained much of its historic architecture. The Middle GroundOriginally just a narrow sandbar between Hudson and Athens, the Middle Ground Flats became more of an obstacle as the 19th century wore on. The Army Corps of Engineers used it as a dumping ground for dredge spoils, and the sandbar grew into an island. In 1845 the steamboat Swallow wrecked on what would become known as "Swallow Rocks" near the flats. In 1874 the Hudson Athens Lighthouse was built to warn mariners away from the flats. Even the Hudson-Athens Ferry, which had to make its way around the lighthouse and the flats, sometimes had trouble, on one foggy occasion striking the lighthouse. As the island built up, it became a popular camping and hunting location for Hudson and Athens residents, in particular because ownership of the island was nearly as muddy as its banks. The BridgeThe plan to build a bridge between Hudson and Catskill began in January, 1930, only a few months after the Black Friday stock market crash of 1929. The bridge that became known as the Rip Van Winkle Bridge was built in the depths of the Great Depression. Originally vetoed by then-Governor of New York Franklin D. Roosevelt, a new governmental organization was created to help fund the construction - the New York State Bridge Authority. With authorization from Albany to issue bonds, to be repaid by the collection of tolls, NYSBA began construction of the bridge in 1932. It was completed in 1935.

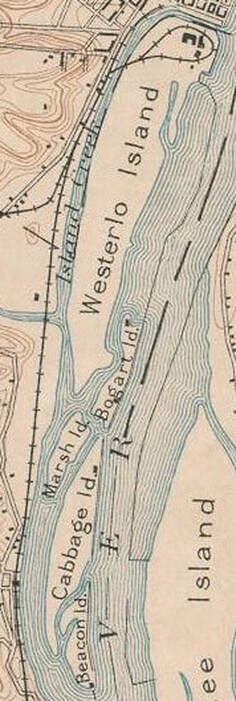

The completion of the bridge signaled the end of ferry service between Hudson and Athens and contributed to the decline of their once-bustling waterfronts.  In this highly romanticized painting by Hudson River School artist Robert Weir, Henry Hudson and his crew are depicted landing at Verplanck Point in Westchester County. Considerably south of Albany, this image is nevertheless typical of 19th century depictions of Hudson's voyages. "Landing of Henry Hudson, 1609, at Verplanck Point, New York" by Robert Weir, 1835. Public domain. Since we are staying in Albany for the day, we thought we should take some time to discuss the very earliest history of Albany and environs - its Indigenous history. Our North Hudson Voyage travels through Mohican lands, which includes Albany and the Capitol District. Mohican people came out to meet Henry Hudson as he approached the Albany region in late September, 1609. The Half Moon ran aground several times attempting to continue north. In one of their more peaceful encounters with Indigenous residents of the river valley, the crew of the Half Moon eat and trade with Mohican people near Albany before heading back downriver to return to the Netherlands. Despite this peaceful encounter, Henry Hudson and his crew maintained a prejudice against the Indigenous people of the valley. In the surviving excerpts from his journal, Hudson notes that he "dare not" trust them. His first mate, Robert Juet, indicates in his surviving log that on September 20, 1609, "And our Master and his Mate determined to trie some of the chiefe men of the Countrey, whether they had any treacherie in them." The crew got them drunk on distilled liquor to see what they would do, but the incident caused no violence from either side and the crew continued to trade with the Mohican people the next day. Over the next few days, smaller boats headed miles upriver, but the waters north of present-day Albany were too shallow for the Half Moon to continue. Disappointed in his failure to find the Northwest passage, Hudson and his crew headed back down river. When Hudson returned to the Netherlands, he reported good timber and fur trading and a navigable river and claimed the valley for the Dutch, despite it already being inhabited. In 1614, the Dutch East India Company sent Adriaen Block to verify Hudson's reports and map the country. That same year, they established a trading post at what came to be called Castle Island. The area now referred to as Westerlo Island was once five separate islands: Castle Island/Westerlo Island, Cabbage Island, Bogart Island, Marsh Island, and Beacon Island. In 1614 the Dutch built Fort Nassau under the command of Hendrick Corstiaensen on Castle Island, but the fort was destroyed by flooding in 1618. Later it became part of the Rensselaerswyck patroonship and was farmed. In 1624 the replacement to Fort Nassau, Fort Orange, was built in what is now present-day Albany. A dispute with the Rensselaers meant that Fort Orange, was considered separate from the patroonship. The fur trading post at Castle Island and those established by the Dutch throughout the Hudson Valley depleted the wildlife stock in the region. Tensions arose between the Mohican and their western neighbors the Mohawk as both were competing for dwindling resources. The coming of the Dutch changed the Mohican way of life as the drive for furs meant increasing dependence on European goods. Introduced diseases like smallpox, diptheria, and scarlet fever decimated indigenous tribes throughout the Eastern seaboard, but as they had some of the earliest contacts with Europeans, Lenape/Delaware and Mohican people of the Hudson Valley were among the most affected. By the 1700s the Mohican had been pushed from the Western shores of the Hudson River, eastward into present-day Massachusetts and Connecticut.

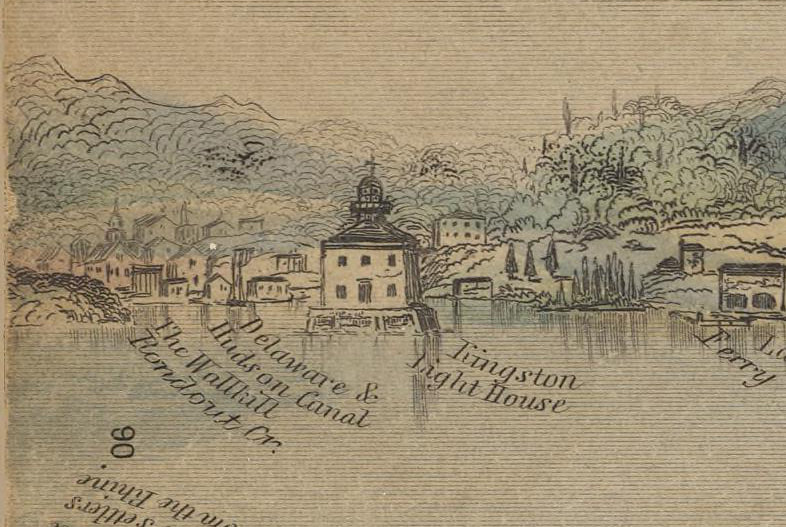

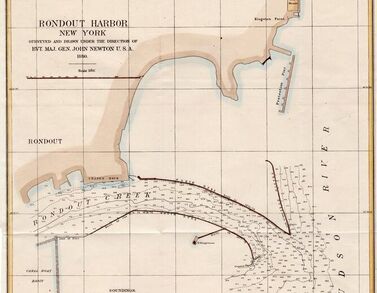

As Dutch settlers moved into the area, European ideas of land use meant that Mohican people were often pushed off of their lands unwillingly, even when a "sale" had taken place. Moving eastward, many Mohican people settled in the Housatonic River Valley. An English missionary named John Sergeant came to live with them in the 1730s and by 1738 he had convinced them to allow him to build a mission, which the Europeans called Stockbridge. Many Mohicans converted to Christianity and were thereafter called "Stockbridge Indians." Many indigenous people, including the Mohican, Oneida, and Tuscarora fought in the American Revolution on the side of the colonists. But their rewards for doing so were few and far between. The Mohican in particular found themselves returning from war, having lost many warriors in battle, to find that plans were underway to remove them from Stockbridge, their own village, where Europeans had decided they were no longer welcome. They found refuge for a time with the Oneida, who in the 1780s invited them to their lands in the Mohawk River Valley. But the reprieve was not to last. By the turn of the 19th century Indian removal policies in New York had begun. Throughout the first half of the 19th century the Mohican people moved and were removed several times, ultimately settling in Wisconsin, on negotiated Ho-Chunk and Menominee territory. Joined by Munsee people there, they became known as the Stockbridge-Munsee tribe. Having weathered the turbulent and destructive 19th century, the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians, like many Indigenous people, still exist. Although most continue to live in Wisconsin, they make frequent trips back to the Hudson Valley to visit their ancestral lands. If you would like to learn more about their history, please visit the Stockbridge-Munsee website, which provided much of the information for this post. And as we travel through Mohican territory, let us remember that the history of this region did not start with the Dutch. This beautiful Hudson River School painting by Rondout resident Jervis McEntee illustrates the mouth of Rondout Creek c. 1840 (note the tiny Rondout Lighthouse at the entrance to the creek - it was built in 1838). You'll note that the wide vista entrance to the creek is much different than it is today. Sloops and schooners were able to approach at a wider angle, allowing them to sail right up the creek. In this detail, you can better see the entrance to the creek and the lighthouse. The tall, full sails of a sloop propel it out toward the Hudson, where a steamboat and other sailing vessels go by. The two story Rondout Lighthouse looks tiny in comparison. Here is another view of the Rondout Lighthouse in 1845. The perspective is not quite the same, although you'll note the ferry landing at right and the inscription "Delaware & Hudson Canal" near the lighthouse. The lighthouse was replaced in 1867 and the site moved slightly to the south. But as steamboat towing traffic increased, and the use of sloops and schooners decreased (but did not disappear) in the latter half of the 19th century, the mouth of the Rondout Creek needed "improvement." Deeper drafted vessels like larger passenger steamboats and the new screw-propelled tugboats needed a deeper river channel. Although Rondout Creek is a natural deep water port, the combination of tidal action and silt from spring floods had left the mouth of the creek shallower than desired. In 1877, the Army Corps of Engineers began a dredging and improvement project that included the construction of breakwater sea walls far out into the Hudson. Where previously, shallower-drafted vessels could take a wide approach into the creek, they now were blocked by the installation of the breakwaters. Completed in 1880, with the dredge spoils dumped behind the walls, the "shallows" were now much shallower, and impassable by all but the smallest of vessels. The narrow approach made it much more difficult for sailing vessels to get in and out of the creek, and even some steamboat captains had trouble.

In addition, the 1867 lighthouse - marked on the map above - was now well behind the entrance to the creek. Red stake lights were installed at each side of the mouth and on the north curve of the breakwater walls, but boatmen complained the lighting was inadequate. In 1915 the old lighthouse was replaced with a new one, right on the north point of the breakwater walls. As Solaris and Apollonia leave Rondout on the North Hudson Voyage, we will pass along those breakwater walls, still in place and still maintained by the Army Corps of Engineers. Fair winds and bright sun - the adventure begins! |

AuthorThis Captains' Log is kept by the captains and crew of Solaris and Apollonia and staff of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed