|

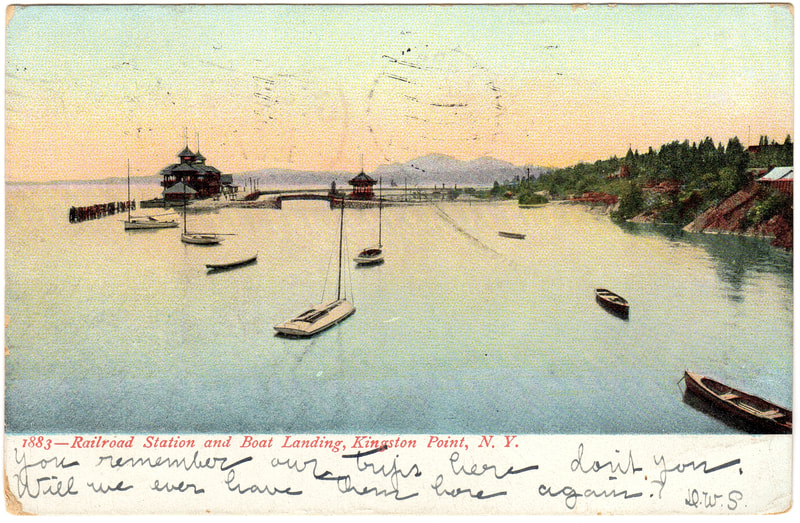

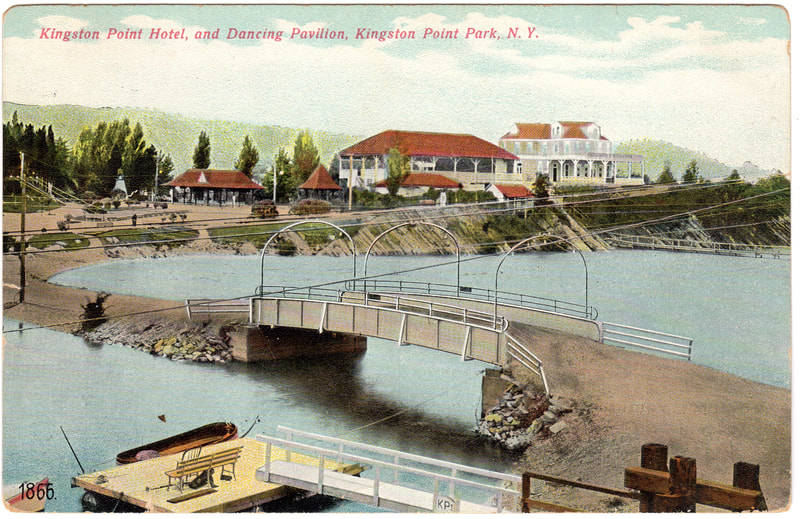

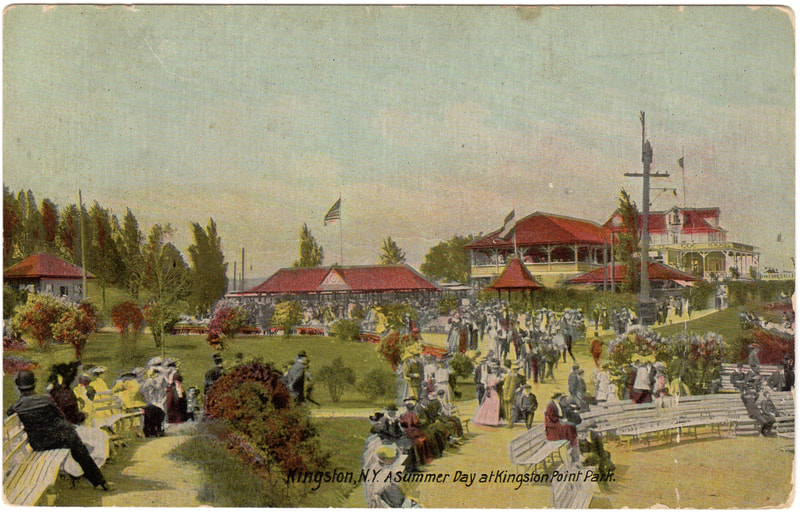

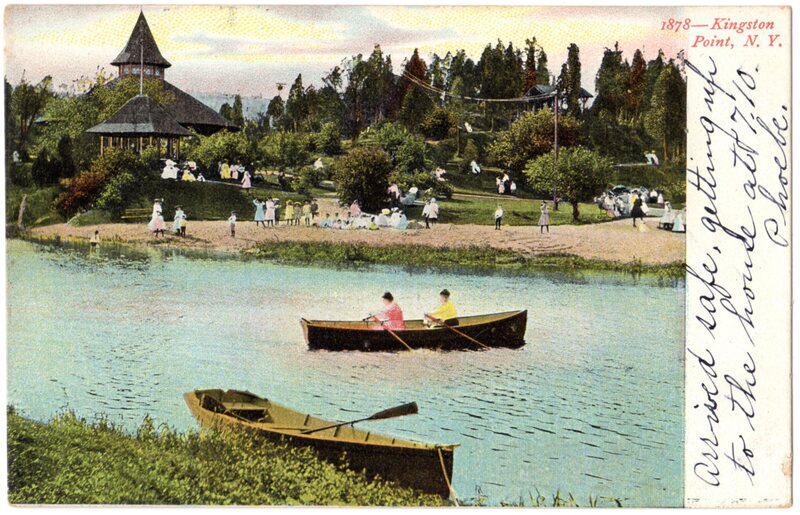

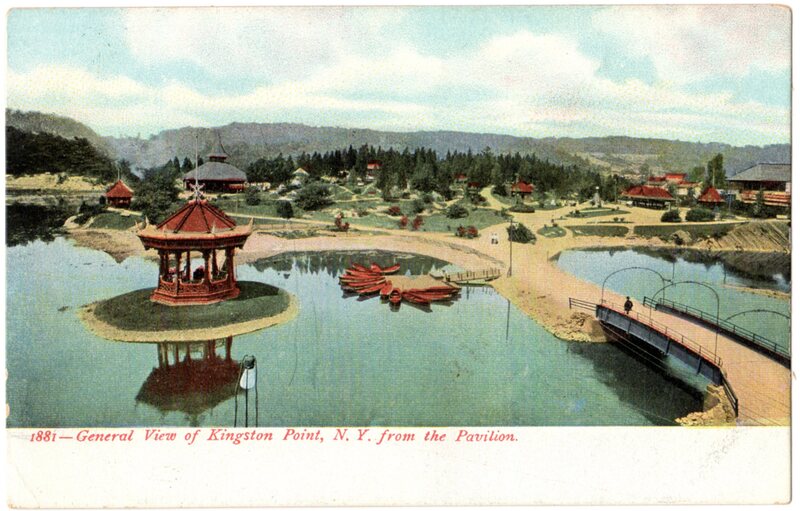

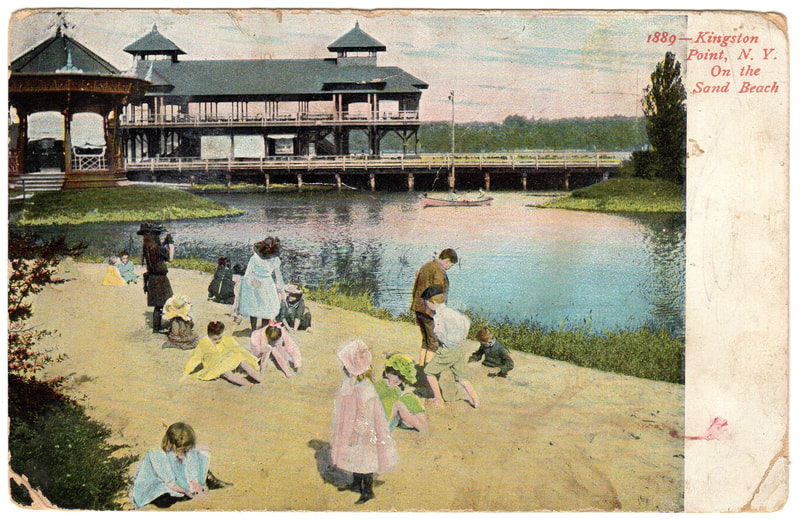

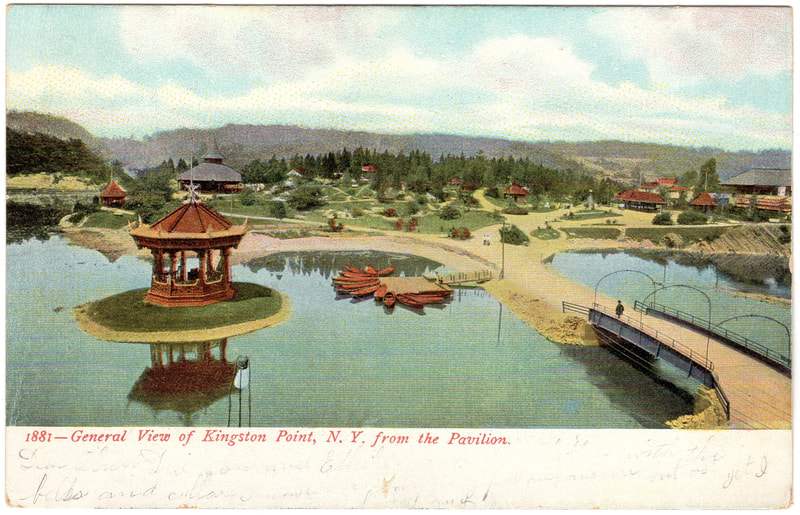

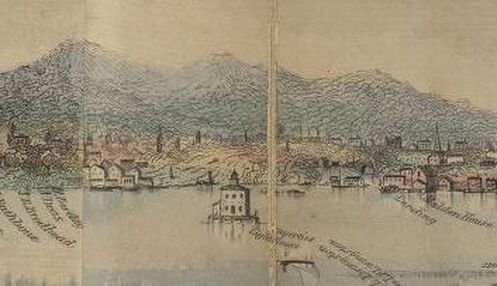

Kingston Point - the closest point to the eastern shore of the Hudson for Kingston and Rondout, had long been used for ferry service. In the 19th century, steamboats generally docked at Rhinecliff on the eastern side, or up Rondout Creek. As steamboats grew larger, the need for a river port increased. In 1896, Kingston Point Park opened with a steamboat landing to entice the Hudson River Day Line steamboats to dock on the Kingston side instead of at Rhinecliff (where the train station was). Built by Samuel Coykendall, heir to the Thomas Cornell Steamboat Company - once the largest towing company on the Eastern seaboard - and owner of the Ulster & Delaware Railroad, the park featured gardens, an amusement park complete with Ferris wheel and carousel, and boat rentals. Serviced by Coykendall's trolleys and Ulster & Delaware railroad trains, visitors docking at Kingston Point Park could take the train up to the Catskill Mountain houses - a popular destination - or take the trolley down to the Rondout Waterfront or walk to the nearby hotel to stay overnight. A fire in the 1920s destroyed most of the buildings. Today, just the park itself and the trolley tracks remain. We thought we'd share just some of the many lovely postcards from the Hudson River Maritime Museum's collection today. Dating to the turn of the 20th century, they illustrate the steamboat dock, boating bay, island bandstand, hotel, trolley tracks, carousel, and park-like grounds. Kingston Point Park was one of over a dozen steamboat landing parks, picnic grounds, and amusement parks that once lined the banks of the Hudson River. We hope to tell more of their stories over the next year and on future voyages!

Do you have a favorite Hudson River park? Share it in the comments!

0 Comments

Acquired from the Esopus (a northern tribe of the Lenape/Delaware nation) by Barent Cornelis Volge in the 1650s, he operated a sawmill there, supplying lumber for the Rensselaerwyck. Between 1659 and 1663 the region was rocked by a series of violent incidents between the Dutch colonists and Esopus Lenape known as "The Esopus Wars." In 1664, the Dutch surrendered their colonial claim on the region to the English, and New Netherland became New York.

In the 1710s German Palatines settled in the area north of Saugerties known as West Camp (East Camp was across the Hudson) to produce pine pitch and tar for the British Navy. The endeavor largely failed, and most of the Palatines moved on. The region continued to be exploited for lumber and a number of saw mills were established over the 18th century. The hamlet of Saugerties was officially established in 1811, though it did not get the name Saugerties until 1855. Throughout the 19th century Saugerties became an industrial hub, with an iron works established in the 1820s and a series of paper mills in the 1830s. Bluestone quarrying and shipment, brick making, and ice harvesting were other major industries in the area. Although the village had passenger steamboat service as early as the 1830s, it wasn't until the 1880s that the Saugerties and New York Steamboat Company was established in the village, providing homegrown steamboat access. Many of the paper mills, especially the Martin Cantine Paper Company (1870s-1970s) continued in operation until the mid-20th century, when industrial manufacturing declined throughout the Hudson Valley. Saugerties is also the location of the Saugerties Lighthouse. First built in 1835 to mark the entrance to the Esopus Creek, the lighthouse was replaced in 1869 with the current structure, which still stands.

We stopped at the lighthouse yesterday to record some interviews, so stay tuned for a new video on the Saugerties Lighthouse coming soon! In the meantime, you can check out this documentary film from the Saugerties Lighthouse Conservancy.

See you this afternoon in Kingston!

Our second-to-last day on the water, we had a shift change for Solaris captains! Captain Jack Weeks, HRMM board member and one of the original promoters of constructing Solaris at the Hudson River Maritime Museum, took the helm from John Phelan.

We also got a chance to show off some amazing drone footage of New Baltimore, with some historical narration.

Poor Captain John didn't get much of a day off today! After seeing Solaris at Germantown, she lost her dingy, "Old Crab," who went on a bit of an adventure! Captain John tracked her down, with a little help.

We ended the day in Saugerties, and even got to talk to the Saugerties Lighthouse keepers, Patrick and Anna Landewe. Stay tuned for more interview footage from them!

Tomorrow is our last day on the water. If you've enjoyed this voyage, please consider making a donation to support this and future voyages.

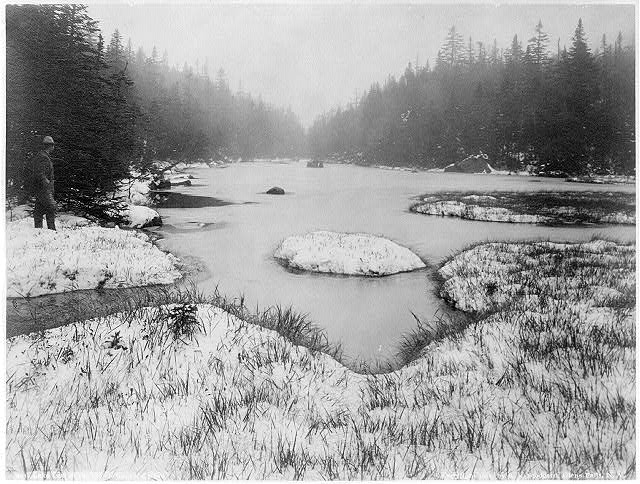

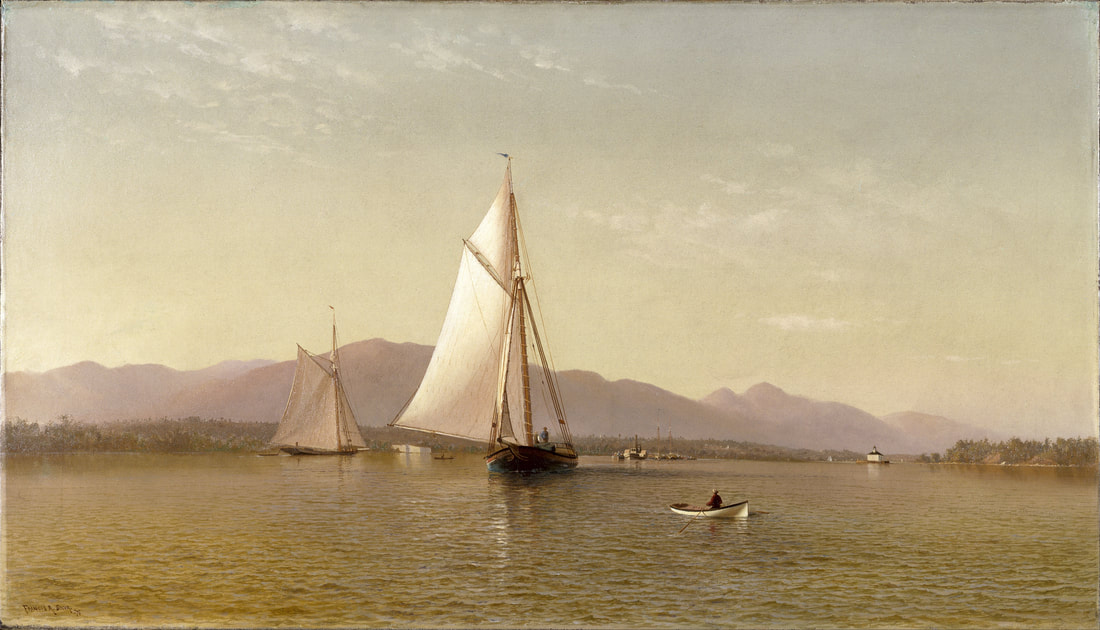

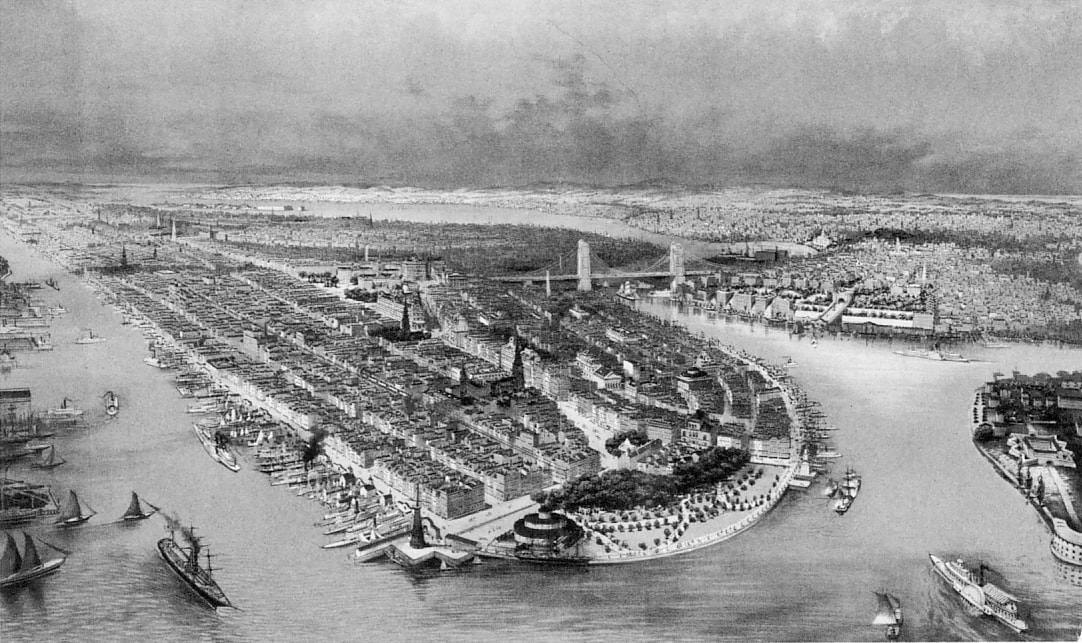

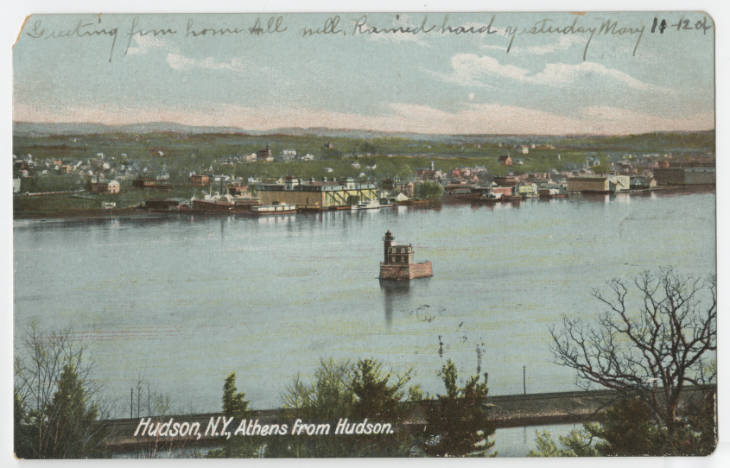

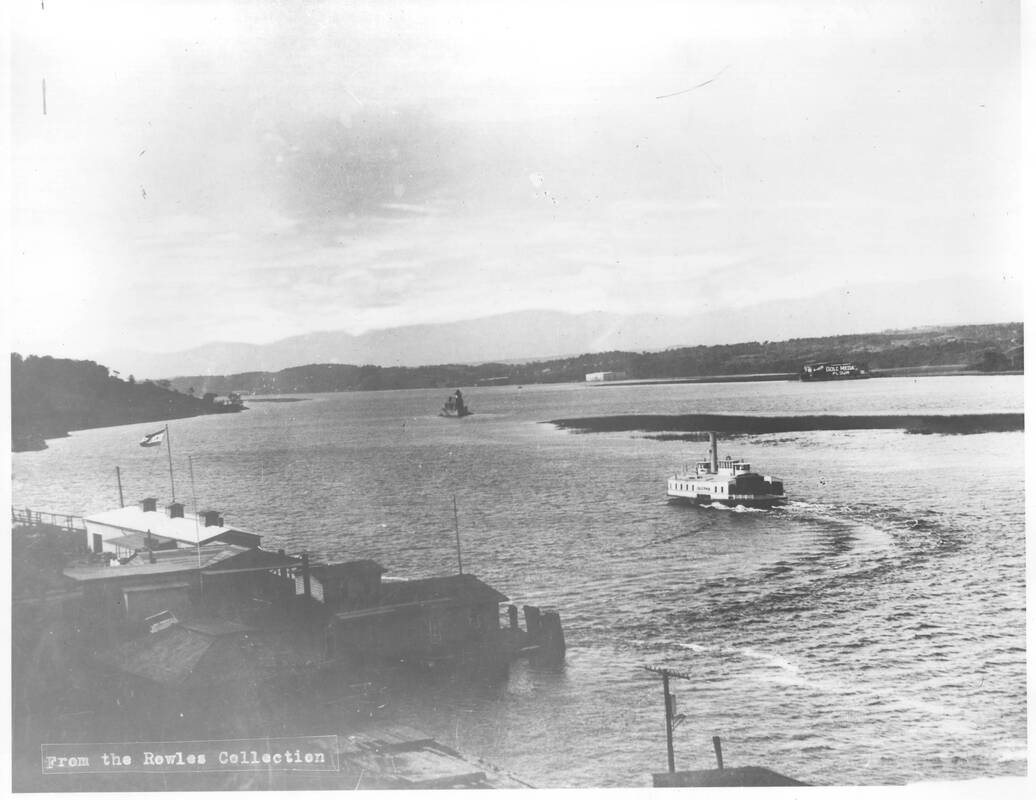

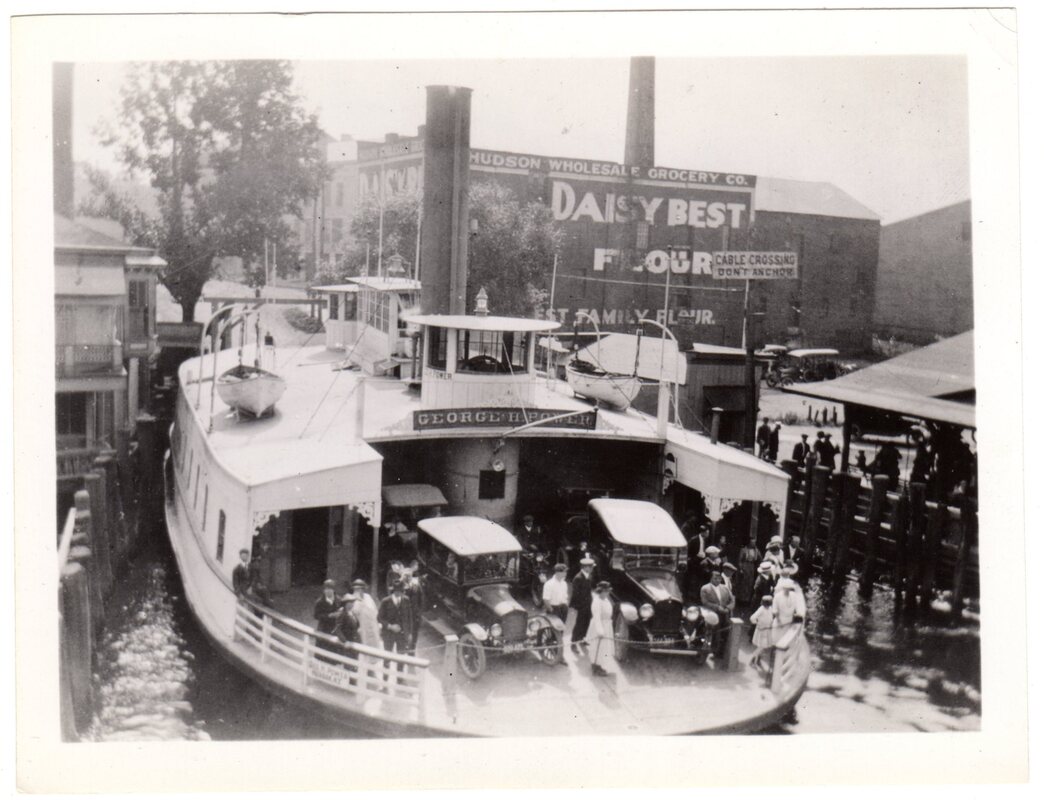

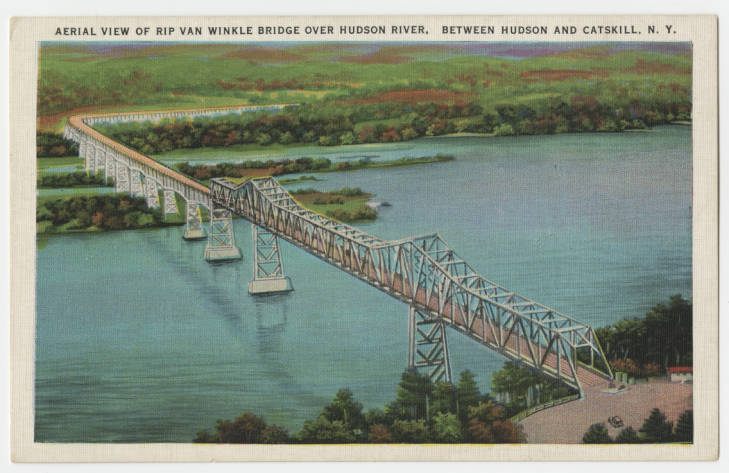

The Hudson, the River that flows both ways has been a transportation corridor for hundreds of years before Europeans first saw it. The Hudson rises in the mountains at Lake Tear of the Clouds in Essex County, NY and empties into Upper New York Bay. The Hudson is a drowned river as its bottom is below sea level almost all the way to Albany. The Hudson is also considered a fjord one of very few in North America. The River has been a commerce highway for as long as humans have inhabited the North American continent. Henry Hudson and other early European explorers were convinced that the River was part of the Northwest Passage. The Hudson River once formed a bustling highway linking even the smallest communities to a web of regularly scheduled commercial routes. Schooners, sloops, barges, and steamboats provided a unique way of life for early river town inhabitants. Farmers, merchants, and oystermen relied on this vibrant and diverse fleet of vessels to bring in supplies and deliver their goods to market. This arm-of-the-sea was an integral part of the lives of those who worked New York’s inland waters. The Hudson is connected through New York Harbor to the Coast and the rest of the world. With one of the world’s greatest ice-free harbors on earth, New York City was built on a shipping industry that has over time become a dangerously tenuous lifeline to the outside world for the region. Today the far-flung international trade network that once pumped vibrant economic life into the region threatens to collapse as imported natural resources and the fossil fuels needed to transport them become increasingly scarce and expensive. Higher petroleum costs, and higher wages in countries in which much of our imported goods are made could snap that lifeline. New York State’s working waterfronts have long been a key contributor to the region’s financial well-being and our nation’s economy. But, in a carbon constrained future, how will goods and people be moved from place to place, and what role will the Hudson River play in this vision? How should we meet the looming challenges of climate change, rising sea level, aging infrastructure, changes to global shipping patterns, threats to food security, and the risks these changes bring to New York’s Hudson Valley. The biggest question of all: How do we address this daunting multitude of challenges and turn them into opportunities for transforming waterfronts and ports to effectively and efficiently serve our regional economy far into the future? The solution in this time of rapid change may be a return to the “Slow Technology” of our recent past — sail powered freight ships – and to the present, solar powered ferries and barges. Tomorrow, New York City’s port and the ports of the Hudson Valley will likely continue to be a commercial hubs due to their strategic location, but those harbors will likely resemble their 18th and 19th century selves rather than the ports we know today. Over the course of the last week, the Schooner Apollonia, and the Hudson River Maritime Museum’s 100% solar electric passenger vessel Solaris embarked on an adventure, Riverwise: North Hudson Voyage, which served as a bridge between the maritime technology of the past into the future. Along the way, we hope you learned about how these apparently divergent technologies can help to bring maritime transport into the future, the history of shipping, ship building, and commerce that once was and will be again an important part of our Hudson River communities. Although the schooner and solar technology seem diametrically opposed, they are actually two converging technologies that are models for the future-proof vessels that will be built and rebuilt locally. Apollonia and Solaris are future-proof sailing, alternative fuel, and solar electric ships that are locally and sustainable built/rebuilt from recycled and renewable materials, and provide training in maritime skills, ship building, and longshore trades while also educating their crews in “earth care, people care, and fair share” principles We hope the "RiverWise: North Hudson Voyage" has served to engage the public and commercial interests along the Hudson in how these two important examples of 19th and 21st Century technology will create opportunities for communities to re-examine how their waterfronts will be used for recreation, conservation, and commerce. This voyage of discovery is the first of many with more and more ships joining this flotilla of hope and inspiration. The next step will be even more critical, to commit to honestly confronting challenges, while also boldly embracing opportunities and possibilities. We must move forward quickly and vigorously, and we need to do more. We must inspire individuals, communities, local leaders, city and state governments to commit to creating a thriving, post carbon transportation and logistics system. We must also commit to the creation of a network of sustainable blue waterways in a region that advocates for a post carbon transition that people will embrace as a collective adventure, as a common journey, as something positive, and above all, as a future full of Hope. AuthorAndrew Willner is the Executive Director of the Center for Post Carbon Logistics https://postcarbonlogistics.org, an instructor at the Museum’s Wooden Boat School, and a member of the Museum’s development Committee. We spent the night at Athens, and as we get underway for our second-to-last day of the North River Voyage, we thought we would talk a little bit about the history of this river town, her sister city across the river, and the middle ground in between. AthensThe village of Athens is located on the west bank of the Hudson at the mouth of Murderer's Creek. Settled as early as the mid-1600s by Dutch colonists on Mohican land, Athens was originally called "Lunenberg" and the name "Murderer's Creek" may be a corruption of the Dutch words for mother or muddy. But the discovery of the body of a young woman on its banks in 1813 cemented its name in local lore. In 1815, Athens applied for incorporation with the state under its new name, inspired by the famous ancient city in Greece. Throughout the 19th century, it was home to shipbuilding, brickyards, and ice harvesting. Sometimes overshadowed by its larger sister city to the east, Athens has maintained much of its historic character, including the preservation of two Dutch colonial houses - the Albertus Van Loon House and Jan Van Loon House. HudsonAlso a colonial Dutch settlement founded on Mohican land, Hudson was once known as Claverack Landing. When New Netherland became New York, Quaker whalers from New England moved to Hudson to escape the privations of coastal pirates. Processing whale oil and ambergris out at sea, the ocean-going whaling ships sailed up to Hudson with their cargoes. Whale oil was a huge business in the 18th and early 19th century and many early lighthouses were lit by whale-oil lamps. But by 1819 the last whaling ship had sailed out of Hudson. The Hudson River Railroad was constructed in 1850, essentially cutting many east shore Hudson River port cities off from the river. In Hudson, the railroad tracks cut off the two bays that had once held so many sailing ships. Only small fishing and recreational vessels were able to leave the harbors .Access to docks and wharfs continued over grade crossings and eventually bridges. But Hudson was transitioning to an industrial manufacturing town. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, Hudson was an industrial port city, with iron works and foundries, brickyards, cement factories, and more. Hudson was chartered as a city in 1785 and thrived until the 1970s, when like many industrial Hudson River towns it suffered economic decline. As with Athens, Hudson has retained much of its historic architecture. The Middle GroundOriginally just a narrow sandbar between Hudson and Athens, the Middle Ground Flats became more of an obstacle as the 19th century wore on. The Army Corps of Engineers used it as a dumping ground for dredge spoils, and the sandbar grew into an island. In 1845 the steamboat Swallow wrecked on what would become known as "Swallow Rocks" near the flats. In 1874 the Hudson Athens Lighthouse was built to warn mariners away from the flats. Even the Hudson-Athens Ferry, which had to make its way around the lighthouse and the flats, sometimes had trouble, on one foggy occasion striking the lighthouse. As the island built up, it became a popular camping and hunting location for Hudson and Athens residents, in particular because ownership of the island was nearly as muddy as its banks. The BridgeThe plan to build a bridge between Hudson and Catskill began in January, 1930, only a few months after the Black Friday stock market crash of 1929. The bridge that became known as the Rip Van Winkle Bridge was built in the depths of the Great Depression. Originally vetoed by then-Governor of New York Franklin D. Roosevelt, a new governmental organization was created to help fund the construction - the New York State Bridge Authority. With authorization from Albany to issue bonds, to be repaid by the collection of tolls, NYSBA began construction of the bridge in 1932. It was completed in 1935.

The completion of the bridge signaled the end of ferry service between Hudson and Athens and contributed to the decline of their once-bustling waterfronts.

The crew had their first rainy night of the voyage, which meant a less than restful night. But a little morning yoga helped make things a little better.

Captains Sam and John discuss the evening's rain and the favorable winds coming toward the valley and the ebb tide in their favor.

Apollonia ship's dog Hoku had a chance to take the helm!

Remember the cute tugboat Betty June? We stopped to talk with her owner Van Calhoun. This is just a teaser for the film to come!

Finally, we know a lot of you have been very curious about how Solaris actually runs on solar panels, so by popular demand, Captain John takes you on a tour of her electrical systems.

We ended the day in beautiful Athens, NY.

And, as a bonus, here's a little tour of Nine Pin Cider Works up in Albany! Apollonia took on cargo from them to bring south to Hudson today.

Hope you've been enjoying the voyage so far. Only a few more days to go!

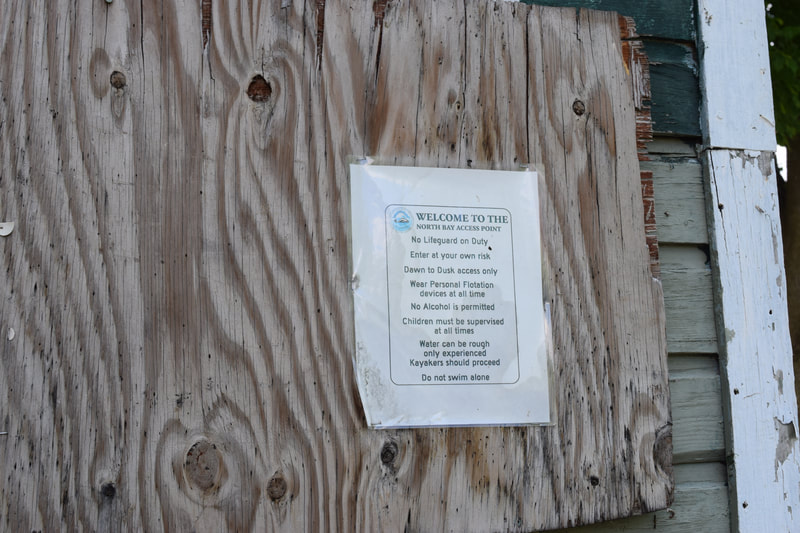

Also known as the "Furgary Fishing Village" or "Shantytown," the fishing village on the southern edge of North Bay in Hudson, NY dates back to the late 19th century. Most of the fishing shacks that remain there now were built between 1930 and 1960. The other week we went up to interview Leo Bowen, who grew up fishing and smoking shad and herring with his father and has been instrumental in helping to prevent the fishing village from destruction. One of the few remaining places on the Hudson River waterfront that illustrate the history of the working Hudson, Leo and other folks in Hudson are trying to restore some of the shacks. We're working on a film of the Shantytown, but thought we would share some of the photos we took while we were there. Lots has been written about the fishing village and shantytown in recent years. Here's a compilation of some of the articles where you can learn more about the village and the attempts to save it:

“Six Things to Know about Hudson's North Bay Shacks” Hudson River Zeitgeist, July 31, 2015 “Tales from Hudson’s Shantytown” The Other Hudson Valley, June 7, 2017 “A Visit to the Furgary” The Gossips of Rivertown, July 8, 2017 “Preserving a Cluster of Fishing Shacks from Hudson’s ‘Forgotten’ Past” New York Times, October 31, 2017 “Saving a Shantytown? In old fishing shacks, links to Hudson’s past and an unclear future” Hill Country Observer, May 2018 “Furgary Boat Club & Shantytown” A Secret History of American River People, 2018 One of the things Leo talked about when we visited was his fond memories of "Nacky," also known as Everett Nack. Nack was a commerical fisherman, unlike many of the men who lived at the fishing village, who fished primarily for themselves or their friends and families. The Hudson River Maritime Museum is lucky to have many oral histories of Hudson River commercial fisher men, including one in which Everett Nack was interviewed in the 1980s. We have digitized these oral histories and have posted some of them online at New York Heritage - a digital repository for historical organizations and libraries throughout New York State.

We had an eventful day yesterday and captured lots of amazing footage! We started out the morning at Scarano's Boatyard in Albany.

Before we left port we had a little fun with Apollonia's delivery tricycle.

Captain John of Solaris gave us a little lesson in tugboats as we left the Port of Albany.

Then Tanya gave us a little history of Castleton and the Castleton-on-Hudson Bridge.

The Apollonia crew was getting a workout this morning beating into a strong headwind. Captain Sam said some of the crew got a little seasick!

Soon the tide turned against them and Apollonia had to anchor. Here is Captain Sam diving in to illustrate the power of the current.

Here's Captain John with a recap of the day. We got some great footage and interviews in Albany and we're looking forward to more as we move south back down the river!

And finally, to end the day, here's a little compilation video from footage we captured yesterday of Apollonia sailing.

We hope you've been enjoying the North Hudson Voyage! For live updates, be sure to follow us on Facebook. And there's still time to donate to support the trip, either by the mile or give what you can.

Solaris and Apollonia spent the night rafted with Clearwater in Albany.

We spent the day in and around Albany, meeting all sorts of friends along the way!

We went up to visit the USS Slater and met up with Clearwater near the Dunn Memorial Bridge for a short fleet sail.

We also had some fun with a kids' project hosted by Tanya, one of our on-board educators. More of these are coming, so stay tuned!

We have been conducting interviews with folks all along this trip, so we got to have a little preview of the films to come today!

First was an interview with Louise Bliss and Don Hagerman who are involved in the restoration of the 1903 racing sloop Eleanor. After a decade of hard work, Eleanor went in the water just last week! Stay tuned for more information and videos about this fascinating project.

We also got some beautiful drone footage and a sneak peak of the Hudson-Athens Lighthouse! We'll be interviewing historians there and getting some interior shots this week as we head back down river. So stay tuned for more!

This trip really has two missions - did you know? One is to bring the Hudson River closer to you with livestreams and social media posts and short videos like these while the voyage is underway.

The second mission is to collect interviews and footage all along the way, so that we can produce a series of short documentary films once we get back! If you would like to support these efforts, please consider sponsoring one of our for themes for this trip: lighthouses, sail freight, towing, and shipbuilding.

And finally, here is our end-of-day video, closing out Day Three of the North Hudson Voyage! Thanks to everyone who has donated by mile and to some brand new sponsors (who we'll be announcing soon)!

See you tomorrow and stay tuned for more on those interviews mentioned in the video!

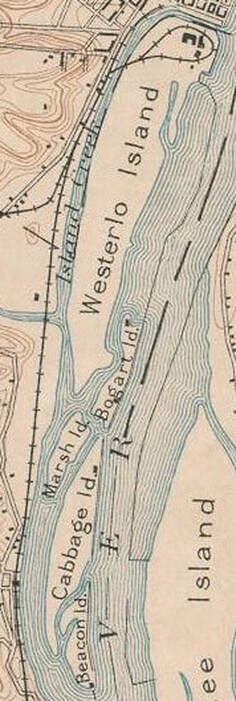

In this highly romanticized painting by Hudson River School artist Robert Weir, Henry Hudson and his crew are depicted landing at Verplanck Point in Westchester County. Considerably south of Albany, this image is nevertheless typical of 19th century depictions of Hudson's voyages. "Landing of Henry Hudson, 1609, at Verplanck Point, New York" by Robert Weir, 1835. Public domain. Since we are staying in Albany for the day, we thought we should take some time to discuss the very earliest history of Albany and environs - its Indigenous history. Our North Hudson Voyage travels through Mohican lands, which includes Albany and the Capitol District. Mohican people came out to meet Henry Hudson as he approached the Albany region in late September, 1609. The Half Moon ran aground several times attempting to continue north. In one of their more peaceful encounters with Indigenous residents of the river valley, the crew of the Half Moon eat and trade with Mohican people near Albany before heading back downriver to return to the Netherlands. Despite this peaceful encounter, Henry Hudson and his crew maintained a prejudice against the Indigenous people of the valley. In the surviving excerpts from his journal, Hudson notes that he "dare not" trust them. His first mate, Robert Juet, indicates in his surviving log that on September 20, 1609, "And our Master and his Mate determined to trie some of the chiefe men of the Countrey, whether they had any treacherie in them." The crew got them drunk on distilled liquor to see what they would do, but the incident caused no violence from either side and the crew continued to trade with the Mohican people the next day. Over the next few days, smaller boats headed miles upriver, but the waters north of present-day Albany were too shallow for the Half Moon to continue. Disappointed in his failure to find the Northwest passage, Hudson and his crew headed back down river. When Hudson returned to the Netherlands, he reported good timber and fur trading and a navigable river and claimed the valley for the Dutch, despite it already being inhabited. In 1614, the Dutch East India Company sent Adriaen Block to verify Hudson's reports and map the country. That same year, they established a trading post at what came to be called Castle Island. The area now referred to as Westerlo Island was once five separate islands: Castle Island/Westerlo Island, Cabbage Island, Bogart Island, Marsh Island, and Beacon Island. In 1614 the Dutch built Fort Nassau under the command of Hendrick Corstiaensen on Castle Island, but the fort was destroyed by flooding in 1618. Later it became part of the Rensselaerswyck patroonship and was farmed. In 1624 the replacement to Fort Nassau, Fort Orange, was built in what is now present-day Albany. A dispute with the Rensselaers meant that Fort Orange, was considered separate from the patroonship. The fur trading post at Castle Island and those established by the Dutch throughout the Hudson Valley depleted the wildlife stock in the region. Tensions arose between the Mohican and their western neighbors the Mohawk as both were competing for dwindling resources. The coming of the Dutch changed the Mohican way of life as the drive for furs meant increasing dependence on European goods. Introduced diseases like smallpox, diptheria, and scarlet fever decimated indigenous tribes throughout the Eastern seaboard, but as they had some of the earliest contacts with Europeans, Lenape/Delaware and Mohican people of the Hudson Valley were among the most affected. By the 1700s the Mohican had been pushed from the Western shores of the Hudson River, eastward into present-day Massachusetts and Connecticut.

As Dutch settlers moved into the area, European ideas of land use meant that Mohican people were often pushed off of their lands unwillingly, even when a "sale" had taken place. Moving eastward, many Mohican people settled in the Housatonic River Valley. An English missionary named John Sergeant came to live with them in the 1730s and by 1738 he had convinced them to allow him to build a mission, which the Europeans called Stockbridge. Many Mohicans converted to Christianity and were thereafter called "Stockbridge Indians." Many indigenous people, including the Mohican, Oneida, and Tuscarora fought in the American Revolution on the side of the colonists. But their rewards for doing so were few and far between. The Mohican in particular found themselves returning from war, having lost many warriors in battle, to find that plans were underway to remove them from Stockbridge, their own village, where Europeans had decided they were no longer welcome. They found refuge for a time with the Oneida, who in the 1780s invited them to their lands in the Mohawk River Valley. But the reprieve was not to last. By the turn of the 19th century Indian removal policies in New York had begun. Throughout the first half of the 19th century the Mohican people moved and were removed several times, ultimately settling in Wisconsin, on negotiated Ho-Chunk and Menominee territory. Joined by Munsee people there, they became known as the Stockbridge-Munsee tribe. Having weathered the turbulent and destructive 19th century, the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians, like many Indigenous people, still exist. Although most continue to live in Wisconsin, they make frequent trips back to the Hudson Valley to visit their ancestral lands. If you would like to learn more about their history, please visit the Stockbridge-Munsee website, which provided much of the information for this post. And as we travel through Mohican territory, let us remember that the history of this region did not start with the Dutch. |

AuthorThis Captains' Log is kept by the captains and crew of Solaris and Apollonia and staff of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed