|

The Port of Rondout, as the Kingston waterfront was once known, was a bustling place for much of the 19th century. That was due in large part to the Delaware & Hudson Canal, which connected to Pennsylvania coal country in Honesdale, PA and terminated at Rondout, with the last (or rather, the first) lock at Eddyville.

The D&H Canal officially opened in 1828, but the Rondout to Port Jervis section opened in 1827. With the increased canal traffic and influx of anthracite coal, Rondout boomed. The easy availability of coal also meant that there was a ready source of inexpensive fuel for steamboats. So while the early days of cargo transportation coming out of the Port of Rondout was primarily by sail freight, steam freight soon began. In the 1830s, Thomas Cornell came with a sailing sloop to Rondout to ship coal from the D&H Canal. A native of White Plains, N.Y. Cornell was just twenty-two years old. Until then, sailboats had done the work of carrying freight and passengers, but Cornell saw that steam-powered vessels were the future. In a few years, he became the owner and operator of steamboats running between Rondout and New York. Cornell settled in Rondout, where he established the Cornell Steamboat Company. In those booming years of growth and construction, there was plenty of business for steamboats plying the Hudson. New York City’s thriving metropolitan area needed coal from the D&H Canal, ice that was harvested in winter from the frozen river, building material produced in the mid-Hudson valley, brick, lumber, stone, and cement – and agricultural products grain, livestock, dairy, fruit, and hay – which came from near and far. Rondout Creek offered the best deep-water port in the Hudson Valley, and thus became the center of maritime activity between New York and Albany. The Cornell Steamboat Company made its headquarters in Rondout village, where many boats were berthed and repaired, and some were built. Between 1830 and 1900, few harbors of comparable size anywhere in America were as busy as Rondout Creek. By the mid-1800s, the Hudson River had many sidewheel steamboats passing north and south, one grander than the other. They carried both freight and passengers, and speed was of the essence – both for bragging rights and because passengers favored the fastest boats. In the 1860s, Thomas Cornell acquired Mary Powell, the Hudson River’s fastest and most beautiful passenger boat. In this time, Cornell built a magnificent sidewheeler to ply the route from Rondout to New York. She was named in his honor – Thomas Cornell - and was one of the finest vessels operating on the Hudson. Steamboats not able to compete in speed or luxury often were turned into towboats, hauling loaded barges that were lashed together to be towed up or down the river. Cornell began to develop a fleet of towboats, which in time would be replaced by tugboats, designed and built especially for towing on the river. After the Civil War, Cornell was joined in the business by Samuel D. Coykendall, who became his son-in-law as well as a partner in the firm. The combination of Thomas Cornell and S.D. Coykendall soon would create the most powerful towing operation on the Hudson River. At its peak in the late 1800s, the Cornell Steamboat Company ran more than sixty towing vessels and was the largest maritime organization of its kind in the nation. Early in 1890, after contracting pneumonia, Thomas Cornell died at home at the age of 77. In son-in-law S.D. Coykendall, Cornell had a worthy successor. During a career of more than fifty years, Thomas Cornell built a mighty business empire and became a leading figure in New York and the nation. In addition to running the Cornell Steamboat Company and the Kingston-Rhinecliff ferry, he built and operated railroads on both sides of the Hudson, helped establish two banks, was a principal in a large Catskill Mountain hotel, and served two terms in Congress. By 1900, the Cornell Steamboat Company had given up the passenger business and turned completely to towing. There were more than sixty steam-powered towing vessels and tugboats in the Cornell fleet. Their boilers were fired by burning coal. Cornell vessels were well-known on the river, with their familiar black and yellow smokestacks clearly recognizable from the northern canals to New York harbor. As the years passed, S.D. Coykendall gave his six sons positions of authority and management in the Cornell business empire. “S.D.”, as he was known, was the leading citizen of Ulster County, heading up banks, developing railroads, operating a hotel and a ferryboat line, and building and operating trolley lines and an amusement park. He invested in many enterprises, including cement works, the ice industry, brickyards, and quarrying operations. In January 1913, S.D. Coykendall died suddenly at this home in Kingston at the age of seventy-six. Frederick Coykendall, who was forty years of age, succeeded his father as president of the Cornell Steamboat Company. Frederick lived in New York and was active in alumni and trustee affairs at Columbia University. He would become chairman of the university’s board of trustees and president of the university press. Assisting Frederick Coykendall was company vice president C.W. “Bill” Spangenberger, who had risen through the ranks since joining Cornell in 1933. When Frederick passed away in 1954, Spangenberger became president. Although company executives worked hard and with considerable success to rebuild Cornell, they were forced to sell out in 1958 when their largest customer, New York Trap Rock Corporation – a producer of crushed stone – offered to buy the company. Trap Rock retained Spangenberger as president of Cornell. In 1960, the Cornell Steamboat Company built Rockland County, an innovative, push-type towboat – the first of its kind in permanent service on the Hudson River. With Rockland County, a new age of towing began on the Hudson, but there would be no future for Cornell. Trap Rock soon acquired by a larger corporation, and the towing company was no longer needed. In 1964, the Cornell Steamboat Company finally closed its doors, after making Hudson River maritime history for an unprecedented one hundred and thirty-seven years.” [Editor's note: Portions of this article were originally published in the 2001 issue of the Pilot Log, the journal of the Hudson River Maritime Museum.]

8 Comments

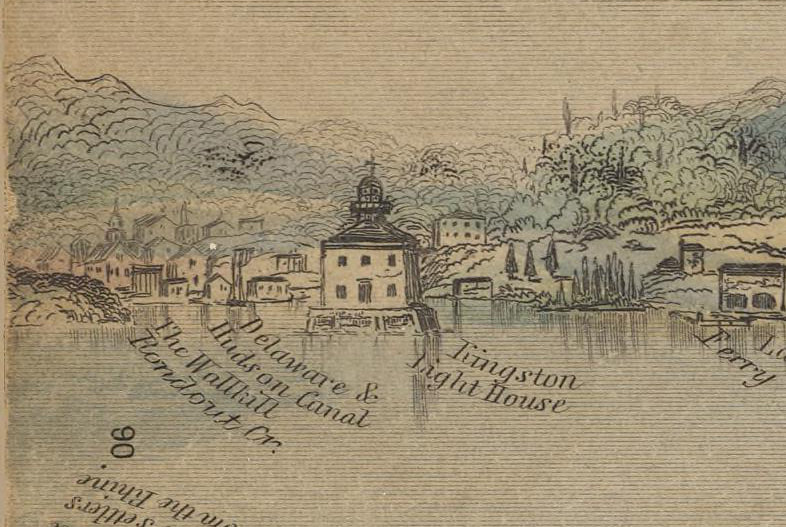

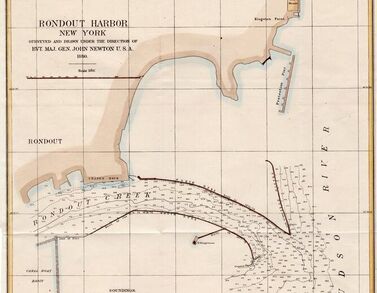

This beautiful Hudson River School painting by Rondout resident Jervis McEntee illustrates the mouth of Rondout Creek c. 1840 (note the tiny Rondout Lighthouse at the entrance to the creek - it was built in 1838). You'll note that the wide vista entrance to the creek is much different than it is today. Sloops and schooners were able to approach at a wider angle, allowing them to sail right up the creek. In this detail, you can better see the entrance to the creek and the lighthouse. The tall, full sails of a sloop propel it out toward the Hudson, where a steamboat and other sailing vessels go by. The two story Rondout Lighthouse looks tiny in comparison. Here is another view of the Rondout Lighthouse in 1845. The perspective is not quite the same, although you'll note the ferry landing at right and the inscription "Delaware & Hudson Canal" near the lighthouse. The lighthouse was replaced in 1867 and the site moved slightly to the south. But as steamboat towing traffic increased, and the use of sloops and schooners decreased (but did not disappear) in the latter half of the 19th century, the mouth of the Rondout Creek needed "improvement." Deeper drafted vessels like larger passenger steamboats and the new screw-propelled tugboats needed a deeper river channel. Although Rondout Creek is a natural deep water port, the combination of tidal action and silt from spring floods had left the mouth of the creek shallower than desired. In 1877, the Army Corps of Engineers began a dredging and improvement project that included the construction of breakwater sea walls far out into the Hudson. Where previously, shallower-drafted vessels could take a wide approach into the creek, they now were blocked by the installation of the breakwaters. Completed in 1880, with the dredge spoils dumped behind the walls, the "shallows" were now much shallower, and impassable by all but the smallest of vessels. The narrow approach made it much more difficult for sailing vessels to get in and out of the creek, and even some steamboat captains had trouble.

In addition, the 1867 lighthouse - marked on the map above - was now well behind the entrance to the creek. Red stake lights were installed at each side of the mouth and on the north curve of the breakwater walls, but boatmen complained the lighting was inadequate. In 1915 the old lighthouse was replaced with a new one, right on the north point of the breakwater walls. As Solaris and Apollonia leave Rondout on the North Hudson Voyage, we will pass along those breakwater walls, still in place and still maintained by the Army Corps of Engineers. Fair winds and bright sun - the adventure begins! |

AuthorThis Captains' Log is kept by the captains and crew of Solaris and Apollonia and staff of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed